By Asia Samachar Gurnam Singh

By Gurnam Singh | Opinion |

Reflecting on the current state of Sikhs worldwide, especially in Punjab, I’m often struck by a painful yet honest observation. While we’ve made commendable strides in fields like agriculture, the armed forces, politics, business and public service, we haven’t yet reached our full potential in law, journalism and my own field, academia.

A 2023 study by Sunny Dhillon, titled “Sikh Panjabi Scholars,” reported that Sikhs are significantly underrepresented in UK academia, particularly in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. Only 0.3% of academics identify as Sikh, making them the lowest represented religious group in UK higher education, with over 50% fewer postgraduate research participants than the next lowest group.

This striking disparity is further highlighted by a more recent study by Professor Harjinder Singh of the University of Warwick, who found that “Sikh PhD students account for the tiniest minority of religious groups studying a PhD in UK universities.” This is particularly concerning given our rich intellectual traditions established by the Sikh Gurus. Indeed, as the following extract from a Shabad by Guru Nanak in Maru (GGS, 1255) states, achieving higher levels of consciousness is intertwined with research and scholarship:

ਮਨਿ ਭਾਵੈ ਸਬਦੁ ਸੁਹਾਇਆ ॥ The Word of the Shabad is so very beautiful; it is pleasing to my mind.ਭ੍ਰਮਿ ਭ੍ਰਮਿ ਜੋਨਿ ਭੇਖ ਬਹੁ ਕੀਨੇ੍ ਗੁਰਿ ਰਾਖੇ ਸਚੁ ਪਾਇਆ ॥੧॥ ਰਹਾਉ ॥ The mortal wanders lost in various guises, wearing various robes and clothes; when he is saved and protected by the Guru, then he finds the Truth. ||1||Pause||ਤੀਰਥਿ ਤੇਜੁ ਨਿਵਾਰਿ ਨ ਨ੍ਹਾਤੇ ਹਰਿ ਕਾ ਨਾਮੁ ਨ ਭਾਇਆ ॥ He does not try to wash away his angry passions by bathing at sacred shrines. He does not love the Name of the Lord.ਰਤਨ ਪਦਾਰਥੁ ਪਰਹਰਿ ਤਿਆਗਿਆ ਜਤ ਕੋ ਤਤ ਹੀ ਆਇਆ ॥ He abandons and discards the priceless jewel, and he goes back from where he came.ਬਿਸਟਾ ਕੀਟ ਭਏ ਉਤ ਹੀ ਤੇ ਉਤ ਹੀ ਮਾਹਿ ਸਮਾਇਆ ॥ And so he becomes a maggot in manure, and in that, he is absorbed.ਅਧਿਕ ਸੁਆਦ ਰੋਗ ਅਧਿਕਾਈ ਬਿਨੁ ਗੁਰ ਸਹਜੁ ਨ ਪਾਇਆ ॥੨॥ The more he tastes, the more he is diseased; without the Guru, there is no peace and poise. ||2||ਸੇਵਾ ਸੁਰਤਿ ਰਹਸਿ ਗੁਣ ਗਾਵਾ ਗੁਰਮੁਖਿ ਗਿਆਨੁ ਬੀਚਾਰਾ ॥ Focusing my awareness on selfless service, I joyfully sing His Praises. As Gurmukh, I contemplate spiritual wisdom.ਖੋਜੀ ਉਪਜੈ ਬਾਦੀ ਬਿਨਸੈ ਹਉ ਬਲਿ ਬਲਿ ਗੁਰ ਕਰਤਾਰਾ ॥ The true re-searcher comes forth, and the debater dies down; I am a sacrifice, a sacrifice to the Guru, the Creative Force.

In this extract, Guru Nanak Ji critiques superficial religiosity. True spiritual awakening arises not from external rituals but from an inner resonance with Truth. Sacred pilgrimages and ascetic practices are portrayed as empty when unaccompanied by love for the Divine Name. In contrast, true liberation and inner peace (sehaj) come only through realizing the Guru’s wisdom, which requires deep contemplation and critical reflection, not rhetorical argumentation that can become a ritualistic practice itself.

Shared Histories, Divergent Paths

Sikhs are often compared to Jewish communities, and for good reason. Both peoples have endured immense historical trauma and displacement. Both are numerically small compared to other world faiths. Both are deeply rooted in specific homelands—Jews in Israel, and Sikhs in Punjab. Both have significant diasporas, particularly in Western nations, and both have faced genocidal violence and the ongoing threat to their existence, often within hostile or indifferent environments.

And yet, when one surveys the global influence of Jewish scholars, journalists and public intellectuals, the contrast is stark. The absence of a similarly visible Sikh presence among public intellectuals reveals a glaring void. This concern was central to the recent Sikh Studies Conference at the University of Warwick on June 7, 2025, where my dear friend Professor Pritam Singh, in his keynote address, highlighted the striking disparity between the global presence of Jewish public intellectuals and the dearth of Sikh counterparts. His remarks were not an indictment but a call to action.

The Jewish Commitment to Education

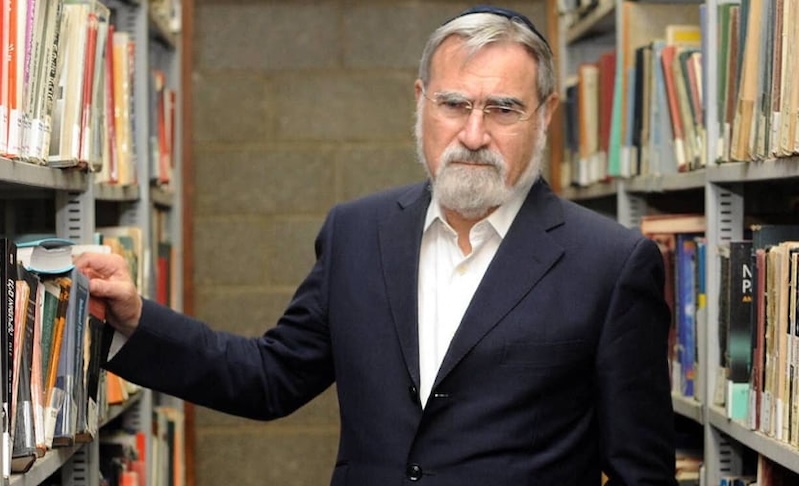

What accounts for this difference? One significant factor lies in the Jewish commitment to education. As the former Chief Rabbi, Jonathan Sacks, once stated: “If you want to save the Jewish future, you have to build Jewish day schools – there is no other way.”

This powerful insight underscores the Jewish understanding that the preservation and flourishing of a people depend not only on faith or memory but on rigorous education, critical thinking and cultural literacy. This commitment is embodied in the Jewish festival of Passover, which cultivates a culture of inquiry, critical thinking and dialogue through its central ritual, the Seder.

At the heart of the Seder is the asking of questions, most famously by the youngest child, symbolizing a communal commitment to curiosity and the transmission of knowledge across generations. The tradition doesn’t shy away from complexity or challenge; instead, it encourages participants to engage deeply with historical suffering, liberation, and moral responsibility. This practice reflects a broader Jewish intellectual tradition that values dissent, debate, and the pursuit of truth as sacred acts.

Literacy Rates and Cultural Orientations

According to UNESCO data, Israel has a literacy rate in excess of 90%, whereas the rate in Punjab is close to 75%. These figures are not merely statistics—they indicate deeper cultural orientations. The Jewish community, despite the traumas of exile and genocide, has consciously invested in educational excellence as a means of collective survival and renewal. Israel, as a nation-state, has harnessed this ethos to produce scholars, scientists and intellectuals of global renown. In contrast, the Sikh community, both in Punjab and across the diaspora, has not yet demonstrated a similar collective commitment to cultivating intellectual capital.

While Sikh communities globally, primarily through the institution of the Gurdwara, remain deeply committed to preserving and transmitting the Punjabi language and, to a lesser extent, scriptural recitation, there is little evidence of a collective effort or desire to engage the younger generation in critical thinking and open questioning. Sadly, attempts to critically explore Sikh history and theology within Gurdwara spaces are often met with suspicion or outright hostility. We appear to be wholly preoccupied with internal disputes, factionalism and parochial power struggles. Instead of investing in knowledge production, we are locked in cycles of infighting that sap our creative potential.

Reclaiming the “Sant-Sipahi” Ideal

Moreover, the dominant narrative of Sikh identity today often rests disproportionately on martial valour. Of course, the Sikh tradition of resistance to tyranny and injustice is something to honour and uphold. But this is only one side of our heritage. Guru Sahib did not merely raise warriors—he also cultivated poets, philosophers, musicians, and mystics. The ideal was always that of the Sant-Sipahi (Saint-Soldier), the warrior-saint/scholar, the one who could wield both the sword and the pen with wisdom and restraint.

As Guru Nanak states,ਧੰਨੁ ਸੁ ਕਾਗਦੁ ਕਲਮ ਧੰਨੁ ਧਨੁ ਭਾਂਡਾ ਧਨੁ ਮਸੁ ॥ ਧਨੁ ਲੇਖਾਰੀ ਨਾਨਕਾ ਜਿਨਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਲਿਖਾਇਆ ਸਚੁ ॥੧॥Blessed is the paper, blessed is the pen, blessed is the inkwell, and blessed is the ink. Blessed is the writer, O Nanak, who writes the True Name. ||1||

Indeed, every time we bow before Guru Granth Sahib Ji – a scripture spanning 1,430 pages of sublime spiritual, ethical and philosophical insight – we are reminded of the central place of learning in our tradition. To be a Sikh, in the most literal sense, is to be a learner. When the Gurus instructed their Sikhs to perform daily “Nitnem,” they didn’t have in mind daily ritualistic praying or chanting, but daily contemplation on Gurbani—on divinity, ethics, reason, spirituality, the meaning of life, nature, the created universe and the creative force.

One of the greatest gifts given to us by our Gurus was the title of Sikhs, which literally translates as learners or seekers. If we truly seek to honor this title, then we must urgently invest in nurturing a new generation of Sikh intellectuals, writers, lawyers, journalists, artists and educators. These are the ones who can build on the legacies established by the Sikh Gurus and so many Gursikhs who followed. Not only can they regenerate our traditions of speaking truth to power, but they will also articulate the relevance of Gurmat across academic disciplines and in public life. And in our quest to survive and thrive, we can learn a lot from our Jewish friends.

Gurnam Singh is an academic activist dedicated to human rights, liberty, equality, social and environmental justice. He is an Associate Professor of Sociology at University of Warwick, UK. He can be contacted at Gurnam.singh.1@warwick.ac.uk

* This is the opinion of the writer and does not necessarily represent the views of Asia Samachar.

RELATED STORY:

The Demise of the Akali Dal and the Badal Dynasty: What Next for the Panth? (Asia Samachar, 5 Aug 2024)

ASIA SAMACHAR is an online newspaper for Sikhs / Punjabis in Southeast Asia and beyond. You can leave your comments at our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. We will delete comments we deem offensive or potentially libelous. You can reach us via WhatsApp +6017-335-1399 or email: asia.samachar@gmail.com. For obituary announcements, click here