Skip to main content

Live Science

Live Science

Search Live Science

View Profile

Sign up to our newsletter

Planet Earth

Archaeology

Physics & Math

Human Behavior

Science news

Life’s Little Mysteries

Science quizzes

Newsletters

Story archive

‘Spiderwebs’ on Mars

New blood type discovered

NASA ‘zombie’ satellite

‘God King’ mystery solved

Diagnostic dilemma

Recommended reading

Gamma-ray bursts reveal largest structure in the universe is bigger and closer to Earth than we knew: ‘The jury is still out on what it all means.’

‘People thought this couldn’t be done’: Scientists observe light of ‘cosmic dawn’ with a telescope on Earth for the first time ever

Black Holes

Astronomers discover most powerful cosmic explosions since the Big Bang

Gigantic, glow-in-the-dark cloud near Earth surprises astronomers

James Webb telescope spots tiny galaxies that may have transformed the universe

Black Holes

Monster black hole jet from the early universe is basking in the ‘afterglow’ of the Big Bang

Astronomers spy puzzlingly ‘perfect’ cosmic orb with unknown size and location

Farthest ‘mini-halo’ ever detected could improve our understanding of the early universe

Perri Thaler

28 June 2025

Scientists have discovered the farthest-ever ‘mini-halo,’ a sea of charged particles around a distant galaxy cluster that could reveal unexpected insights about the ancient universe.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

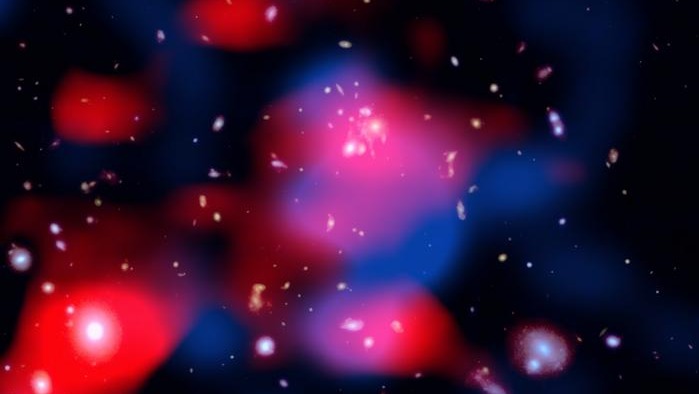

Charged particles of a mini-halo, in red, surround a cluster of galaxies, in white.

(Image credit: Chandra X-ray Center (X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI; Radio: ASTRON/LOFAR; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk))

While analyzing a 10 billion-year-old radio signal, astronomers discovered a “mini-halo” — a cloud of energetic particles — around a far-off cluster of galaxies. The unexpected findings could further our understanding of the early universe.

This mini-halo is the most distant one ever detected, located twice as far from Earth as the next-farthest mini-halo. It is also massive, spanning more than 15 times the width of the Milky Way, and contains strong magnetic fields. The findings have been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and are available on the preprint server arXiv.

“It’s astonishing to find such a strong radio signal at this distance,” Roland Timmerman, a radio astronomer at Durham University who co-led the study, said in a statement.

You may like

Gamma-ray bursts reveal largest structure in the universe is bigger and closer to Earth than we knew: ‘The jury is still out on what it all means.’

‘People thought this couldn’t be done’: Scientists observe light of ‘cosmic dawn’ with a telescope on Earth for the first time ever

Astronomers discover most powerful cosmic explosions since the Big Bang

How did the mini-halo form?

Mini-halos are faint groups of charged particles that emit radio and X-ray waves in the vacuum of space between galaxies. They have been detected around galaxy clusters in the local universe, but never as far back in space and time as the one reported in the new study.

There are two theories that could explain the collection of particles, according to the researchers.

One possible cause is the supermassive black holes at the centers of large galaxies within the distant cluster. These black holes can shoot high-energy particles into space, but it’s not clear how the particles would travel away from a powerful black hole and into a mini-halo without losing significant energy.

Another possible means of creation is the collision of charged particles within the plasma in a galaxy cluster. When these high-energy particles smash into each other, often at close to the speed of light, they can break apart into the kinds of particles that can be seen from Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Contact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

Related: James Webb telescope unveils largest-ever map of the universe, spanning over 13 billion years

Implications for astronomy

Observations of the mini-halo come from light so old that it changes the picture of galaxy formation, proving that these charged particles have surrounded galaxies for billions of years longer than was known.

“Our discovery implies that clusters of galaxies have been immersed in such particles since their formation,” Julie Hlavacek-Larrondo, an astrophysicist at the University of Montréal who also co-led the research, told Live Science in an email. It’s “something which we were not expecting at first.”

Scientists can now study the origin of these mini-halos to determine whether black holes or particle collisions are responsible for them.

These particles also have a hand in other astrophysical processes, like star formation. They can affect the energy and pressure of the gas within a galaxy or couple with magnetic fields in unique ways. These processes can keep clouds of gas from collapsing, in turn altering how stars form in the gas.

RELATED STORIES

—’Totally unexpected’ galaxy discovered by James Webb telescope defies our understanding of the early universe

—Ghostly galaxy without dark matter baffles astronomers

—Astronomers discover giant ‘bridge’ in space that could finally solve a violent galactic mystery

“We are still learning a lot about these structures, so unfortunately the more quantitative picture is still very much in development,” Timmerman told Live Science in an email.

New radio telescopes, like the SKA Observatory, are in development to help astronomers detect even fainter signals and learn about mini-halos.

“We are just scratching the surface of how energetic the early Universe really was,” Hlavacek-Larrondo said.

Perri Thaler

Social Links Navigation

Perri Thaler is an intern at Live Science. Her beats include space, tech and the physical sciences, but she also enjoys digging into other topics, like renewable energy and climate change. Perri studied astronomy and economics at Cornell University before working in policy and tech at NASA, and then researching paleomagnetism at Harvard University. She’s now working toward a master’s degree in journalism at New York University and her work has appeared on ScienceLine, Space.com and Eos.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Gamma-ray bursts reveal largest structure in the universe is bigger and closer to Earth than we knew: ‘The jury is still out on what it all means.’

‘People thought this couldn’t be done’: Scientists observe light of ‘cosmic dawn’ with a telescope on Earth for the first time ever

Astronomers discover most powerful cosmic explosions since the Big Bang

Gigantic, glow-in-the-dark cloud near Earth surprises astronomers

James Webb telescope spots tiny galaxies that may have transformed the universe

Monster black hole jet from the early universe is basking in the ‘afterglow’ of the Big Bang

Latest in Astronomy

Listen to the Andromeda galaxy’s stars played as musical notes in eerie NASA video

Why does Mars look purple, yellow and orange in ESA’s stunning new satellite image?

‘City killer’ asteroid 2024 YR4 could shower Earth with ‘bullet-like’ meteors if it hits the moon in 2032

You can see a giant ‘hole’ shoot across Saturn this summer — and it won’t happen again until 2040

Mysterious ‘rogue’ objects discovered by James Webb telescope may not actually exist, new simulations hint

James Webb telescope discovers its first planet — a Saturn-size ‘shepherd’ still glowing red hot from its formation

Latest in News

World’s oldest rocks could shed light on how life emerged on Earth — and potentially beyond

Scientists discover rare planet at the edge of the Milky Way using space-time phenomenon predicted by Einstein

Listen to the Andromeda galaxy’s stars played as musical notes in eerie NASA video

Still frame from video footage recorded in the Kvænangen fjords, Norway, in 2024, showing the tongue-nibbling interaction between two free-ranging killer whales.

‘It is our obligation to future generations’: Scientists want thousands of human poop samples for microbe ‘doomsday vault’

Why does Mars look purple, yellow and orange in ESA’s stunning new satellite image?

LATEST ARTICLES

Dwarf sperm whale: The ‘pint-size whales’ that gush gallons of intestinal fluid when surprised

Scientists invent weird, shape-shifting ‘electronic ink’ that could give rise to a new generation of flexible gadgets

Are cats the only animals that purr?

Science news this week: A unique new blood type and ‘spiderwebs’ on Mars

Rocks in Canada may be oldest on Earth, dating back 4.16 billion years

Live Science is part of Future US Inc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site.

Contact Future’s experts

Terms and conditions

Privacy policy

Cookies policy

Accessibility Statement

Advertise with us

Web notifications

Editorial standards

How to pitch a story to us

Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street,

Please login or signup to comment

Please wait…