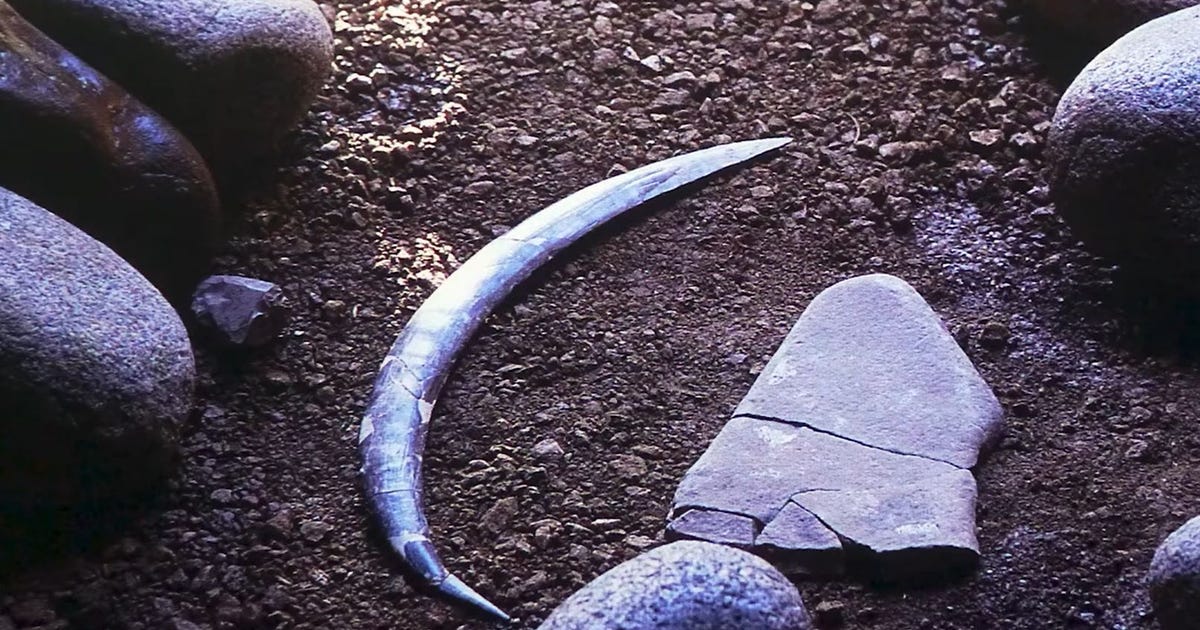

In southern Poland near the border with Slovakia is a cave that was home for hundreds of thousands of years, first for Neanderthals and later for modern humans. Obłazowa Cave has been undergoing excavation since 1985, two years after which a unique find emerged: a boomerang made of mammoth tusk. At the time, the team led by Pawel Valde-Nowak dated it to 23,000 years ago and announced that it was likely the “earliest certain find of this type of weapon in the world.” Which is still true, in the sense that Valde-Nowak and colleagues now reveal that it’s a stunning 40,000 years old and no earlier ones have been reported. The paper on the refined chronology of the site and the boomerang was published Wednesday in PLOS One. Though older than first thought, it remains the theory that it was made by the cave’s modern human occupants, not the Neanderthals. Those would have gone extinct by the time of the Obłazowa’s main occupation phase by modern humans, which Valde-Nowak and colleagues now redate to 43,000 to 38,500 years ago. The boomerang itself was made within that time frame, the team reports. In short the earliest boomerang wasn’t Australian, it was Aurignacian: the earliest modern human culture in Europe, and the earliest known creators in Europe of figurative art. (In southeast Asia, we find earlier cave art from about 54,000 years ago.) Pre-Aurignacian culture is 43,000 to 37,000 years ago, when proper Aurignacian emerged. We won’t argue over whether the boomerang of Obłazowa cave was pre-or-proper Aurignacian, but it was from about that time. The earliest known boomerang found in Australia is a mere 10,000 years old, though there is cave art theoretically dated to about 20,000 years that seems to show boomerang usage. The Aurignacian culture that emerged in southern Europe featured cave paintings that awes us and shames our mean abilities to this very day; and they were also the makers of the earliest known “portable art.” Their figurines featured stunning craftsmanship in stone, bone and ivory of animals, animal-human hybrids, curvaceous and oft exaggerated female shapes and the likes of the Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany, featuring an unmistakable mega-feline face and a human body. This “Lowenmensch” was also made of mammoth tusk and is Aurignacian. That is the rich cultural context in which this object shaped like a boomerang was found. The team calls it a boomerang because it looks like one, not necessarily because they believe it was used the same way the later aboriginal Australian ones were used, Valde-Nowak kindly explained by telephone from his car in Poland. But it may have been. First of all, it was crafted to be flat-convex in cross-section, which is exactly like Queensland boomerangs. In fact, it’s pretty indistinguishable from the Queensland specimens, he adds. Second, what does one want in one’s boomerang? That it fly fast and hard and hit a target. And this thing can fly. Experiments done with a replica show that it flies very effectively, he says, adding that the trajectory is much longer than in the case of a wooden stick that does not feature a crafted flat-convex cross section. “Yes,” he confirms, “it could go much farther than a spear.” Hmm. Sounds useful. We just add that prehistoric hominins in that very area were using spears – though the dating was recently revised from possibly 400,000 years ago to about 200,000. Anyway, spears only go so far, and an Aurignacian could theoretically have used the boomerang to throw very hard at an animal or neighbor who was too far away for a spear to obtain, though if he fluffed it, the boomerang would not return. Like the boomerangs of Queensland, this didn’t return to the thrower. (Despite what people not involved in prehistoric projectiles research and cartoonists think, not all boomerangs are designed to come back.) But in prehistoric Poland, did it serve to do in reindeer – a favorite of the cave occupants, or some other animal to eat, or other people? Or was it a prop for ritual? There is argument to be made for symbolism. “Red ocher is preserved in the cracks, as on other objects that were lying nearby,” Valde-Nowak says. Ocher use for symbolic purposes goes back to the dawn of our species. The earliest known burials, in Israel’s Tinshemet Cave from 100,000 years ago, feature clumps of ocher that may have been used to decorate the tombs or the dead or both. So ocher supports the theory of ritual or symbolic use for the boomerang, but then WWII pilots painted pin-up ladies or fangs on their bombers, and so on. Decoration may not have ruled out a deadly pragmatic use. Further supporting a hypothesis of ritual nature was the nature of its deposit. “Regardless of the possibility of its use as a weapon or an everyday tool, the context of the find indicates exceptional reasons,” the professor says. “It was deposited in a structure made of massive boulders weighing over 60 kilograms, brought to the cave from the bed of a nearby river,” he adds. Also, the material was valuable: mammoth tusk. “This must be treated as something special and valuable for this community; it was beautiful,” he adds. Originally the ivory would have been cream colored and beautifully bright; what the team found is a fossil darkened by the eons and mineralization. So even if it had pragmatic use, in his opinion – the combination of elements whisper of some special ritual aspect or function. Of course the Aurignacians made tools of stone, and wood we presume. But this boomerang was carved with exquisite craftsmanship of precious ivory. “It was not very easy to cut the mammoth tusk and carve it into the form of the boomerang,” he adds. “This is a surprise.” And it is the only one ever found in Paleolithic Europe. Conversely, if it was utilitarian, wouldn’t one expect to find more? Yet no similar objects or suspect fragments have been found until the Mesolithic, from which period boomerangs were unearthed in a peat bog in Denmark. Their absence could be preservation bias – boomerangs wouldn’t be made of stone and one can expect that most, if there were any, decayed and are no more. So what have we? A unique artifact made of a mammoth tusk, which was a material used by artistic Aurignacians, that looks like a boomerang and flies like a boomerang, predates the next known specimen by tens of thousands of years, and was found in the context of some of the first modern human settlers in Poland. Boomerangs would next appear in the archaeological record only about 10,000 years ago, in Denmark and Australia. Supporting the thesis that maybe these things were used more widely in prehistory but we didn’t find them, come the early historic period – the technology was not confined to Central Europe and Down Under. “I would like to point out that Tutankhamen’s grave had some wooden boomerangs, and one of them was made of ivory! With some gold applications – like our ocher! That too points us to the special ritual involving this weapon or flying idea,” Valde-Nowak says. Some call the objects in ancient Egyptian archaeologist “throwing sticks,” but that’s what a boomerang is. Not all have that classic shape we know from the cartoons. What did the ancient Egyptians use boomerangs for? We know that from their art – centuries before Tut’s era, they were using them to hunt birds. Ducks, for instance. Other finds in Obłazowa in the same context include ornaments, pendants and amulets made of arctic fox bone, and flint artifacts made of stone that had to have been brought from 300 kilometers away. And a human thumb bone, which was found near the boomerang, in the center of boulders. Clearly all this mattered deeply to somebody. Could the boulders, the thumb bone and the precious artifact signify that actually, the archaeologists had found an Aurignacian grave with goods? Hard to say. But the indications are that the modern humans didn’t necessarily live in the cave, as opposed to its previous inhabitants, the Neanderthals. “Obłazowa cave was a living space for the Neanderthals,” he says. “We have everyday rubbish in at least seven Neanderthal layers. Then layer 8 is totally different, without the everyday rubbish and elements. This is the Homo sapiens layer – with a totally different character of context and findings.” While the Neanderthals lived there or at least camped there long-term, the humans may not have; but they brought selected items to the cave.Why? Who knows. “Obłazowa Hill can be seen from a long distance, [from] over 50 kilometers [away],” Valde-Nowak says. “Maybe that is also a factor why first the Neanderthals, then the Homo sapiens, repeatedly camped there or visited there.” When looking for it, you can’t get lost.