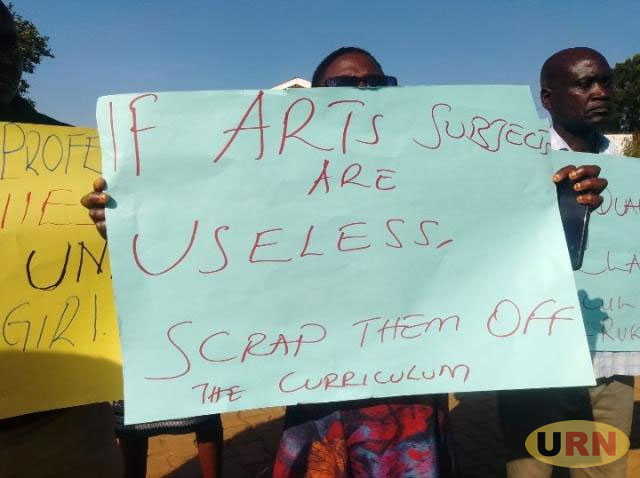

Kampala, Uganda | THE INDEPENDENT | As arts and humanities teachers across Uganda stay away from classes, demanding salary parity with their science counterparts, one voice remains conspicuously silent: UNATU, the Uganda National Teachers’ Union.

Once the most organised and recognised platform for teacher advocacy in the country, UNATU has become noticeably silent, a silence that some members interpret as both betrayal and strategic ambiguity.

Shamim Mukasa, an arts teacher in Wakiso, confirms that most UNATU members remain in classrooms, but would like to join the protests.

“UNATU hasn’t told us to strike,” she says, “but we believe they should be louder, more active, and help increase pressure which has been put up by the new Uganda Professional Humanities Teachers Union.”

The dissatisfaction among arts teachers is rooted in the government’s 2022 decision to award science teachers a staggering 300% pay increase as part of a broader “science-led” development agenda.

UNATU, at the time, had pushed for an equitable distribution of available resources under the rallying cry: All teachers matter. However, science teachers under the Uganda Professional Science Teacher Union, arguing they were more essential to Uganda’s industrialisation goals, broke ranks and formed their union, eventually securing their demands through focused lobbying. The result: science teachers received a major raise, while their colleagues in arts and humanities were left behind.

UNATU made early attempts to challenge the government on pay disparities, but their efforts were repeatedly deflected, most notably during a series of high-level meetings with President Yoweri Museveni. In one such meeting at Kololo, Museveni acknowledged the importance of teachers but bluntly stated that the government “does not make money by witchcraft,” adding that no immediate funds were available for salary enhancements. He suggested that phased increases might be possible in future financial years, a promise that, to date, remains unfulfilled.

Despite continued petitions and threats of industrial action, UNATU’s persistent lobbying yielded few tangible results. This growing sense of inertia and perceived compromise has led to mounting frustration among its membership, especially arts and humanities teachers, who felt left behind after science teachers successfully secured significant pay raises. In response, some teachers have broken away to form another union, convinced that a more confrontational approach could compel government action.

Among these is the newly formed Uganda Professional Humanities Teachers’ Union, which is now spearheading the current wave of strikes. Like their science counterparts, arts teachers are seeking to negotiate independently of UNATU, arguing that the union has become too accommodating to government interests.

Yet, as the strikes unfold, UNATU remains largely on the sidelines, offering neither explicit endorsement nor vocal support, a silence many see as a further sign of its waning influence in the sector.

Vincent Wambokka, the UNATU Kampala Chairperson, says the union is actively engaging the government through formal negotiations, in collaboration with other unions, to advocate for equal pay across all teaching disciplines.

“We’ve taken to the streets before, but we believe that approach may no longer yield the results we need,” he noted, emphasising that UNATU members are fully informed about the union’s ongoing strategy. He also pointed out that a national meeting with branch chairpersons was convened in mid-May to brief them on the union’s position.

In an interview, UNATU Secretary General Filbert Baguma defended the union’s position, stating that teachers expecting action should “follow what UNATU is doing on its platforms,” and blamed misinformation and disengagement among members for the current confusion. He insisted that “UNATU remains committed to all teachers regardless of what or where they teach.”

“All efforts toward salary enhancement have been championed by UNATU since as far back as the 2018 negotiations,” said Baguma. “Our position has always been clear; we want salary enhancement for all teachers at all levels, and that remains our stand.”

He added that while some individuals occasionally feel that UNATU is not vocal enough, they often break away to form separate platforms aimed at pursuing personal or group-specific interests, rather than advancing the collective welfare of all teachers.

UNATU has been consistently lobbying the government to implement a more equitable pay structure for teachers across all disciplines and education levels. Specifically, the union is advocating for a salary of 4.8 million shillings for graduate science teachers and 4.5 million shillings for their counterparts in arts and humanities. In addition, they are pushing for a minimum wage of 1.35 million shillings for primary school teachers.

Currently, however, there remains a stark disparity in the government’s salary structure. Graduate science teachers in secondary schools receive 4 million shillings, while arts and humanities teachers earn approximately 1.07 millionshillings. Diploma-level science teachers are paid 2.2 million shillings, compared to just 780,000 shillings for diploma arts teachers. At the primary level, the average monthly salary stands at around 500,000 shillings, far below the proposed threshold.

Pressed on whether UNATU is losing members and influence due to fragmentation, Baguma remained defiant. “Some of those forming new unions were never members of UNATU to begin with,” he said. He argued that these emerging voices are sometimes driven by short-term grievances and warned that without clear objectives, they may collapse like previous splinter groups, referencing the now-defunct Liberal Teachers Union that faced scandals and arrests.

He did, however, acknowledge growing perceptions of external interference aimed at dividing teacher representation for political or strategic ends: “I cannot confirm or deny it, but where there’s frustration, anything can happen,” he noted.

Despite criticism, Baguma maintained that UNATU “has not moved off-track” and continues to pursue a structured, long-term engagement with the government for sustainable improvements. The union has not endorsed the current strikes but remains, in his words, “focused on what adds value to teaching and learning.”

The Shifting Terrain of Teacher Unionism in Uganda

The roots of teacher organisation in Uganda stretch back to the colonial era. In 1947, the Uganda Teachers Association (UTA) was established under the leadership of John Kissaka, primarily advocating for professional standards in education.

However, internal tensions emerged as a segment of primary and junior secondary teachers felt their welfare needs were not adequately addressed. This led to the formation of a breakaway group, the Primary and Junior Secondary Teachers Union (UPJU), which later rebranded as the Uganda National Union of Teachers (UNUT), signalling a broader, more inclusive focus on all teaching categories and a sharper emphasis on welfare.

For decades, UTA and UNUT operated with parallel mandates, one pushing professionalisation, the other championing economic and labour rights. In 2002, in a bid to consolidate their influence and unify teacher representation, the two groups merged to form the Uganda National Teachers’ Union (UNATU), officially registered in March 2003. This merger was positioned as a new era for teacher advocacy, combining the ideals of professional excellence with the fight for better pay and working conditions.

However, the promise of unity has since faced significant strain. Over the years, UNATU has been repeatedly rocked by internal divisions, often fueled by political interference, ideological rifts, and disputes over transparency. In 2011, the union experienced its first major splintering when over 400 teachers broke away to form the Uganda Liberal Teachers Union (ULITU), citing a lack of accountability and internal democracy within UNATU.

More recent years have seen further fragmentation. In 2022, science teachers, buoyed by government-backed salary enhancements, formed their union, frustrated by what they saw as UNATU’s ineffective bargaining. That momentum has since spread to arts and humanities teachers, many of whom now see UNATU as being too conciliatory with the state. Even private school teachers, once informally aligned with the union’s vision, have formed independent structures to push for sector-specific demands.

What was once a singular voice for Uganda’s Teachers has now become a chorus of competing interests, each vying for attention in a strained and highly politicised educational landscape.