By Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow Nigel Westmaas

“The essence of trade unionism is social uplift. The labor movement has been the haven for the dispossessed, the despised, the neglected, the downtrodden, the poor.”

– A Philip Randolph, American labour unionist and civil rights activist

Since the establishment of the British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU) in 1919, approximately 160 trade unions have operated in Guyana, according to bibliographic records. However, the history of trade unionism in the country is neither straightforward nor conventionally gallant. It has been a complex and often difficult trajectory, shaped by both persistent efforts and significant obstacles. This ongoing struggle has been led by workers seeking to secure rights long withheld from them and has encompassed resistance to exploitative labour practices such as sweatshops, child labour, excessive working hours, inadequate wages, and hazardous working conditions all deeply rooted in the post-emancipation socio-economic context.

The origins of trade unionism are rooted in the broader struggles of workers under global industrial capitalism. Concurrently, as workers in Europe, North America and in the colonised world pushed for better wages and working conditions in the 19th and early 20th centuries, similar efforts began to emerge across the colonial world. In Guyana, the rise of trade unionism was shaped by colonial oppression, racism and racial hierarchies, and the economic and social hardships endured by Africans, Indians, Amerindians and other ethnic groups. These conditions produced a distinctive labour movement that emerged early in the 20th century and played a central role in the country’s path toward political change all the way to independence and beyond.

Long before the BGLU was founded in 1919 there were active indications of worker solidarity. of organised labour attempts in Guyana. For example, the short-lived Boot & Shoemakers Association appeared in Georgetown in 1889, and the Guiana Patriotic Club & Mechanics union followed in the 1890s. By 1903, a proto political group, the People’s Association, called publicly for the formation of a trade union. The call gained traction after the consequential 1905 rebellion, with figures like Dr John Rohlehr publicly supporting a formal trade union while acting as a spokesperson for the dock workers. Still, no union materialized for over a decade, though attempts were made to organise workers. In 1910, miners and others tried to band together, and strikes broke out in 1916.

As noted, the first breakthrough came in 1919 with the founding of the BGLU by Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow and others. From the start, the BGLU viewed itself not just as a trade union but as part of a wider movement for expanded rights, including political rights. This was reflected in its support for the fight for adult suffrage under colonial rule.

Growth and growing pains

The formation of the BGLU was prompted by growing worker solidarity, particularly among dock workers, and the desire to recover from defeats by powerful employers like Sprostons. By 1920, the BGLU had grown rapidly, climbing to some 13,000 members, thanks largely to Critchlow’s charisma and tireless organising. The union secured major victories such as the eight-hour workday for waterfront workers and began to reach into rural areas.

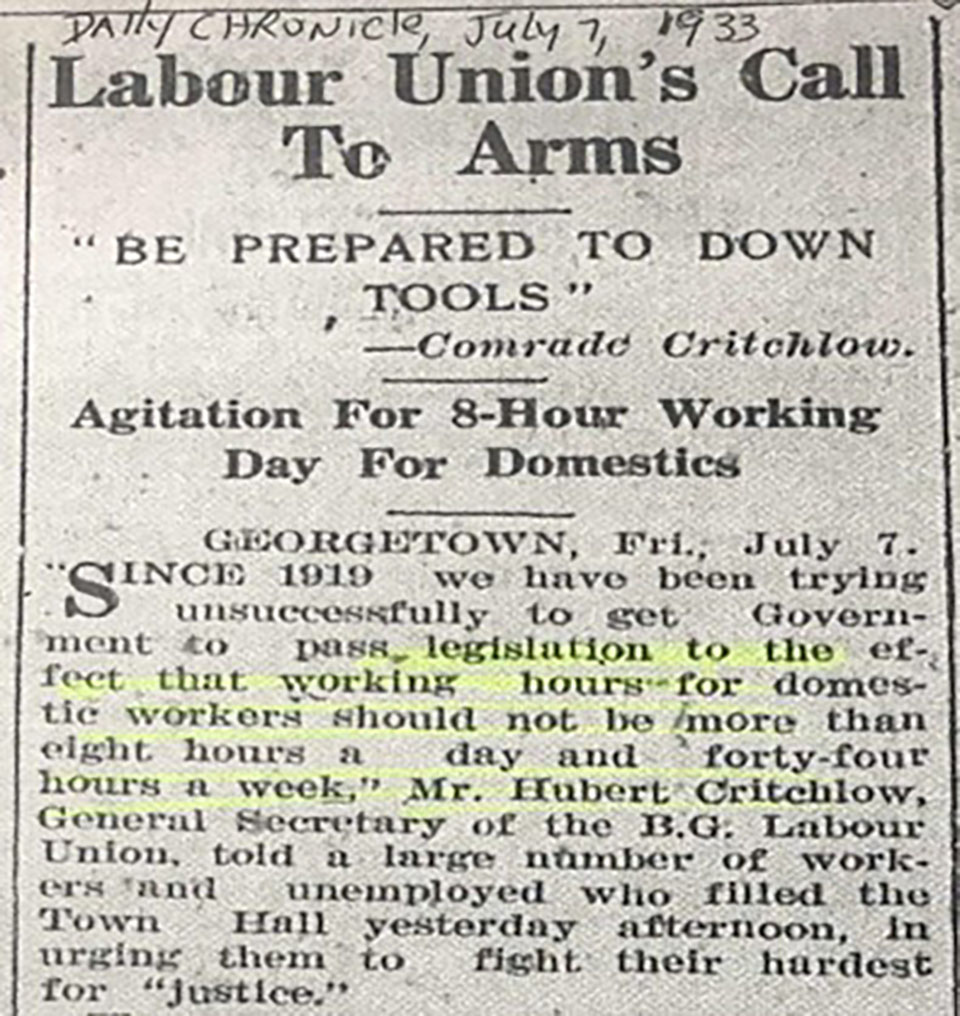

Despite facing challenges, the BGLU remained an important voice in national affairs. It led campaigns for rent controls after rents rose by 80% between 1914 and 1922, pushed back against high living costs, and advocated for better treatment of domestic workers. In 1924, after unsuccessful efforts to secure a minimum wage, protests and unrest spread. While the immediate outcomes were limited, the movement helped strengthen both local and international labour solidarity. That year also marked the union’s first use of picketing as a tactic.

However, internal and external challenges mounted. Financial difficulties were persistent. By 1924, the BGLU’s bank account reportedly held just $5, a stark reflection of the strain of trying to run an organisation on eight cents per week in dues. The mercantile elite and colonial authorities were also active in trying to undercut the union. Employers routinely refused to recognise the union or negotiate, pushing Critchlow to appeal to allies in Britain’s Labour Party. Critchlow himself faced personal attacks, often criticised, paradoxically but not surprisingly, for his working-class roots and clashing with middle-class citizen activists’ rivals like A A Thorne. In 1931, Thorne, the Barbados-born educator, journalist and politician launched the British Guiana Workers League, focused mainly on municipal and public service workers. Though it achieved small successes in improving conditions for hospital workers and running industrial exhibitions, it never grew beyond 500 members.

By the early 1930s, the BGLU was struggling, its membership atrophying. Its youth wing was disbanded in 1929, and political campaigns (such as those for universal manhood suffrage) took a toll.

New entrants

Despite internal divisions, trade unions continued to drive social change in Guyana through the 1930s. May Day rallies organised by the BGLU drew thousands, as in 1935 when workers paraded through Georgetown, passing resolutions on wages, housing, and healthcare. Nigel Bolland in his ‘On the March’ emphasised two noticeable estate incidents in 1935. African strikers with sticks and cutlasses ordered one white overseer “to dance to a drum and when he said he did not know how, they ‘gave an African exhibition dance’ around him, but let him go when armed police arrived.” The second incident was at Plantation Ogle where “shovelmen took an overseer’s saddle off his horse and threw it into a trench. A ‘gang of East Indian and Blacks beat the deputy manager and forced him to carry a red flag at the head of their procession. Between 200 and 300 strikers, ‘waving cutlasses and sticks and carrying red flags’, said they wanted more money…”

In the same year, 1935, in what was described as a “Monster May Day Rally in British Guiana” the Negro Worker (Critchlow served on the editorial board of this Germany-based newspaper) reported on the resolutions passed by Critchlow and others: “Two resolutions – one, a list of demands to be presented to the newly appointed Governor, the other protest against Mussolini’s intention to invade Abyssinia, were passed unanimously.” Among the demands made to the Governor at the time were: legislation for shorter working hours for both skilled and unskilled workers without a reduction in pay; an increase in the primary school leaving age; better housing and lower rents; the introduction of an old age pension scheme; a national health insurance scheme; and universal suffrage.

The Negro Worker reported that “the meeting closed with a collection and among the songs, ‘Africans, Awake’, and the ‘Internationale’ were sung.”

A new player emerged in 1938, the Man Power Citizens Association (MPCA). By 1940, it claimed some 20,000 registered union membership, the largest in the colony. It was led by Ayube Edun. Later Dr Jung Bahadur Singh, a president of the British Guiana East Indian Association (BGEIA), became more active in trade union organising.

The growing unrest and poor labour conditions across the British Caribbean prompted the British government to establish the Moyne Commission in 1938 to “investigate social and economic conditions in Barbados, British Guiana, British Honduras, Jamaica, the Leeward Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Windward Islands, and matters connected therewith, and to make recommendations.” The commission travelled to various colonial territories and took evidence and complaints. The commission’s report confirmed what many on the ground already knew: that poor wages, inadequate housing, limited education, and lack of political representation were driving discontent. While the report recognised the legitimacy of labour grievances, it also recommended a cautious, gradual approach to reform. Yet, the commission’s findings helped validate workers’ demands and gave momentum to calls for social and political change, including improvements in health, education, and labour rights.

In 1941 the British Guiana Trades Union Congress was born. Reconstituted in 1943 it served as an umbrella organisation with then existing 24 trade unions. Critchlow and Theophilus Lee held the two main positions in the TUC.

At Mackenzie, workers also tried to organise unions. In 1942, the BGLU began organising in the region, but visiting Mackenzie required permission due to the racist, exclusionary policies of the companies. Eventually, the MPCA began to take on union efforts, but by 1950 the British Guiana Mineworkers Union (later Guyana Mine Workers union) was registered, with Charles Carter as the union representative, essentially taking over from the MPCA. A bauxite strike occurred in 1947 following two major retrenchments caused by a drop in post–World War II demand for bauxite. There were further bauxite miners’ strikes in the 1970s. Indeed, Odida Quamina made the claim that “nowhere in Guyana was worker consciousness more evident than in the twin communities of Mackenzie and Wismar-Christianburg”.

GIWU to GAWU

In the postwar period, unions remained central to the push for new labour laws and broader social reforms. In 1946, the Guyana Industrial Workers Union (GIWU, later known as GAWU) was founded and would go on to become the country’s largest trade union.

Two major labour disputes followed in April 1948: the transport strike and the Enmore strike that resulted in the murder of five sugar workers who were gunned down by the colonial police. Both had lasting impacts, not just on the labour movement but also on Guyana’s nationalist political struggle. Around the same time, the Venn Commission investigated conditions in the sugar industry (1948–49), further highlighting the challenges faced by workers in the postwar era.

But over time, the movement began to lose its momentum. Rising political factionalism in the 1950s and 60s fuelled by Cold War tensions and internal competition saw unions increasingly pulled into party politics. Leaders like Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham offered conflicting visions of whether unions should stay politically neutral or actively aligned. This development blurred the line between labour activism and partisan politics.

Post independence

The period from the birth of the modern political movement in 1950 to independence saw the dominance of political parties over the trade union movement, which was weakened by ideological and ethnic divisions in Guyanese society. In 1963, one of the country’s longest strikes, lasting 80 days, was called to protest the reintroduction of a second version of the Labour Relations Bill, amid ethnic, political, and Cold War tensions that surrounded a besieged PPP government.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, relations between trade unions, the state, and companies were tense and confrontational. A major flashpoint came in 1977, when the Guyana Agricultural and General Workers Union (GAWU) launched a 135-day strike, the longest in the country’s trade union history. This action responded directly to the government’s 1974 sugar levy, which was seen as unjustly reducing workers’ earnings from the sugar industry. The strike reflected growing dissatisfaction with state economic policies and Guysuco’s management.

At the same time, the bauxite industry saw the emergence of the Organisation of Working People (OWP), a grassroots political and labour movement. It gave voice to bauxite workers who felt marginalised by state-led industrial policy and disillusioned with the formal unions.

Another turning point came with the Teemal vs Guyana sugar Corporation Ltd decision, ruled on by Justice Claude Massiah in 1982. While the details of the case are often overlooked, it marked an important legal precedent for how the courts would treat union representation and worker rights. The 1984 Labour Amendment Act, introduced under Forbes Burnham, deepened the strain between the state and labour. It sharply curtailed the ability of unions to negotiate and strike, further limiting their influence during a time of economic stress and political repression.

These developments illustrated a wider trend of increasing state control over labour, along with a more compliant stance from many unions toward political power.

With the return of the PPP to government in 1992, tensions between the state and labour and labour unions persisted, particularly between the Guyana Public Service Union and the state.

Several factors contributed to the decline of activist trade unionism: ageing leadership, declining membership, economic pressure, and political co-optation. Many unions came to be seen as bureaucratic, stagnant, or too closely tied to political parties to advocate effectively for workers.

Wider changes also mattered. New economic models, shifts in labour markets, and legal constraints from both the state and private companies limited union action. The adoption of labour rights language by state and corporate actors further blurred the lines between genuine advocacy and managed appearances. This, combined with rising individualism in workplace struggles, led to growing public distrust in union leadership.

The crisis has always had an international dimension. Across the global south, Structural Adjustment Programmes in the 1980s and 1990s pushed nation states to reduce public sector jobs, weaken labour protections, and establish free trade zones hostile to unionism.

Global capitalism has reshaped labour markets in ways that systematically undermine trade unions. Through the outsourcing of production, privatization, and the support of anti-union laws, collective labour power has been steadily eroded. While unions continue to resist, they do so in a system that favours profit and competition over fairness and solidarity.

Today, both globally and in Guyana, governments often express symbolic support for trade unionism celebrating past victories in May Day speeches, while simultaneously undermining collective bargaining and labour rights. This contradiction has marked the policies of every Guyanese government since independence.

The recent Guyana Teachers Union teachers’ strike over salaries and other issues and its negative outcome for the teachers underscored the fragile state of collective bargaining, the inconsistency of solidarity, and the atmosphere of fear among both workers and union leaders.

Still, the legacy of leaders like Hubert Critchlow, Ashton Chase, Joseph Pollydore, Richard Ishmael, Andrew ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, Harry Lall, A A Thorne, Jung Bahadur Singh, Leslie Melville, Wilfred Edun, H J M Hubbard, Ivan Edwards, George DePeana, Dr J P Lachmansingh, Jane Phillips-Gay, Gordon Todd, and Komal Chand, and the unions they helped to build, has left a lasting mark on Guyanese society. As Lincoln Lewis, current General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress, remarked in a statement linking past and present:

“There is no Guyanese today in high office, no business owner, employer, or manager, whose success is not tied to the foundation laid by the working class. We are, in the main, descendants of people once deemed inferior, enslaved, indentured, and disenfranchised. The fight for recognition, equality, and justice began with workers standing together, and it is a fight that continues, even as the actors and tactics change.”