By Israel Becomes Muay Masood Lohar

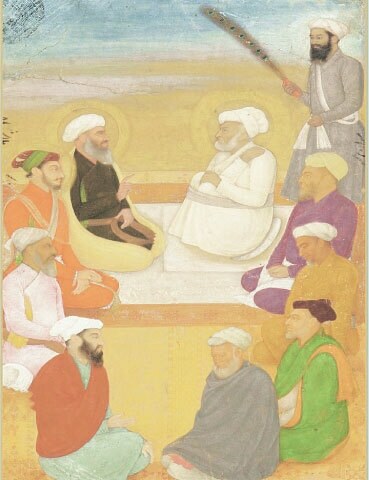

In the shadow of swords and scriptures, one prince stood apart — Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. Destined to inherit the throne, Dara chose the path of spiritual unity over imperial conquest. His execution in 1659 by his brother Aurangzeb marked not only the death of a prince, but the eclipse of a syncretic, inclusive vision for the Indian Subcontinent.

A Sindhi Saint, a Royal Disciple

Dara’s spiritual mentor was Mian Mir, the revered Sufi saint of the Qadiriyya order, whose roots lay in Sehwan, Sindh. Mian Mir was the grandson of Qazi Qadan (1493-1551), the great Sindhi scholar and poet, who laid the early foundations of Islamic and literary traditions in Sindh. His Sindhi heritage and deep mystical teachings shaped Dara’s sensibilities, grounding his intellect in the soil of a multi-religious, poetic tradition.

From Mian Mir, Dara imbibed a worldview rooted in compassion, mysticism and unity. Mian Mir’s own gesture of laying the foundation stone of the Golden Temple in Amritsar at the invitation of Sikhism’s Guru Arjan Dev exemplified the interfaith harmony that shaped Dara’s soul.

Scholar, translator and heir to the Mughal throne, Dara Shikoh was declared a heretic for believing Hindu sages and Sufi saints spoke the same truth. His killing was more than just fratricide…

Dara was also drawn to the wild and fearless Sufi Sarmad Kashani, whose haunting poetry and public defiance of orthodoxy captivated Dara’s imagination. Sarmad was an Armenian Jew-turned-Muslim mystic who wandered Delhi unclothed, immersed in ecstatic visions. These were not mere affiliations — they formed the spiritual DNA of a prince who dared to see the Divine in all paths.

The Mystic Scholar

Dara’s intellectual legacy is staggering. He saw no contradiction between the Quranic vision and Hindu metaphysics. He translated the Bhagavad Gita into Persian and, in his Sirr-e-Akbar [The Greatest Secret], translated 52 Upanishads — Hindu sacred treatises written in Sanskrit c. 800–200 BCE, expounding the Vedas in predominantly mystical and monistic terms — claiming these were the Kitaab al-Maknn [Hidden Book] referenced in the Holy Quran. He dared to place Indic wisdom on a par with Abrahamic traditions, not as a rival, but as a complementary pathway to the same truth.

In his masterpiece Majma-ul-Bahrain [The Confluence of Two Oceans], Dara wrote: “The soul of Vedanta and the essence of Sufism are but two currents flowing from the same ocean.” Dara saw Divine light across temples and mosques alike. He believed in Wahdat al-Wujood [Unity of Being], as taught by Andalusian scholar Ibn Arabi, and saw Haqq [the Truth] not bound by any one faith, but shimmering through all spiritual traditions. For him, spiritual identity was fluid and God’s presence was universal.

Dara also emphasised harmony through dialogues with yogis, Brahmins and Jain monks. In Mukalama-i-Baba Lal Das wa Dara Shikoh [The Dialogues between Baba Lal Das and Dara Shikoh], he records a respectful conversation with the Hindu ascetic Baba Lal Das, demonstrating his deep understanding of metaphysical concepts, such as atman [soul] and Brahman [ultimate reality], and relating them to the Sufi idea of the ruh [soul] and Haqq [ultimate reality].

Orthodoxy Strikes Back — The Sirhindi–Dehlvi Dispute

But Dara’s inclusive mysticism collided with a rising tide of revivalist orthodoxy. Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564-1624), the self-proclaimed Mujaddid Alf-i-Thani [Reformer of the Second Millennium], sought to purify Islam of what he considered syncretic and pantheistic deviations. He rejected Ibn Arabi’s Wahdat al-Wujood in favour of Wahdat al-Shuhood [Unity of Witness] — a stricter separation between the Creator and creation.

In one of his most controversial letters, recorded in Maktubat-i-Imam Rabbani [Letters of Imam Rabbani, Vol. II, Letter 36], Sirhindi described a dream in which he and the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) were both mureeds [spiritual disciples] receiving faiz [favour] directly from Allah, suggesting a spiritual parity in receiving Divine grace. Though he attempted to couch it in reverence, the implication that he stood alongside the Holy Prophet (PBUH) as a co-recipient of Divine emanation was seen as theological arrogance.

This claim sparked outrage among contemporaries, most fiercely from Shaikh Abdul Haq Muhaddis Dehlvi (1551-1642), the era’s leading scholar of hadith [traditions and sayings of the Holy Prophet, PBUH] and a custodian of traditional Sunni orthodoxy. Though careful in naming names, Dehlvi’s rebukes in works such as Madarij an-Nabuwwah [The Majestic Stations of Prophethood] and Akhbar al-Akhyar [The Conduct of the Pious] made it clear: no saint, however elevated, could share in the Holy Prophet’s (PBUH) unique spiritual station. Dehlvi accused such mystical overreach of violating the foundational doctrine of Khatm-i-Nabuwwat [Finality of Prophethood] and breaching spiritual etiquette.

Opposition to Sirhindi’s ideas ironically elevated his standing, casting him as a reformer willing to confront mystical excesses. His emphasis on doctrinal rigour resonated with the future Emperor Aurangzeb’s orthodox leanings.

Sirhindi’s son, Khwaja Muhammad Ma’sum, who succeeded him as the Naqshbandi master, became Aurangzeb’s spiritual guide, mobilising support for him during the war of succession. His deputies and sons were dispatched to back Aurangzeb’s claim, while Ma’sum himself journeyed to Makkah to rally religious endorsement. This alliance between throne and tariqa [Sufi order] would prove decisive.

After executing rivals, including Dara, Aurangzeb wielded orthodoxy as political armour, legitimising his reign through Islamic revivalism while suppressing dissent. His reign thus fused spiritual authority with imperial control, turning Sirhindi’s legacy into a tool for centralised power.

This episode exposed deep tensions: between revivalist reformers and classical scholars, between metaphysical Sufis and legal-minded theologians. Where Sirhindi sought to guard orthodoxy, Dara sought to unveil unity. While one centralised purity, the other embraced multiplicity. Sirhindi’s ideas — carried forward by Ma’sum — would ultimately shape the mind of Aurangzeb, while Dara’s pluralistic dream would be declared dangerous.

The Trial and the Tragedy

In 1659, Dara was defeated in the battle at Deorai near Ajmer. Dragged in chains through Delhi, he was paraded before crowds inflamed by clerics accusing him of apostasy. His trial was a spectacle of coercion — a hastily convened court of scholars declared him a heretic for his translations of Hindu texts and his association with non-Muslims.

The charges: that he translated texts of the infidels, that he believed the Hindu sages held truths equal to those of the Holy Quran, and that he sat in temples and recited “blasphemous” verses in Sanskrit. His writings were held up as evidence of deviation. None spoke of his courage. None mentioned his intent: to bring peace through understanding.

That night, Dara was brutally executed. His severed head was delivered to Aurangzeb, who had it presented to their imprisoned father, Shah Jahan. Dara’s body was quietly buried near Humayun’s Tomb, without honour.

Witnesses recounted that when Shah Jahan saw the head of his son — who had once been his intellectual companion and the favoured heir — he broke down into tears, calling him “the soul of India lost to ignorance and envy.”

Months later, Sarmad Kashani, too, was executed in front of the Jama Masjid in Delhi, on charges of heresy, following Aurangzeb’s order. His blood ran through the streets of Delhi, silencing yet another voice of rebellion to the orthodoxy.

The Dream That Died

Dara’s murder was not merely political — it was the silencing of a vision where Islam and Indic wisdom coexisted, not in tension but in transcendence. His writings — Majma-ul-Bahrain, Sirr-i-Akbar and others — remain as blueprints for spiritual unity.

In Dara’s worldview, India could be a garden of many flowers, where no belief had to dominate, and no seeker needed to fear. In killing Dara, Aurangzeb did not merely eliminate a rival; he killed a possible future.

Dara’s life reminds us that history often crowns the tactician but buries the visionary. Dara might have united India’s soul — had the sword not spoken louder than the pen.

The writer is an activist and founder of the Clifton Urban Forest, Karachi.

X: @masoodlohar

Published in Dawn, EOS, July 6th, 2025