By Shi Huang

The earliest tools used by humans were made of stone, followed by bronze, then iron, and finally steel. But was there a “Wood Age”?

This question has been difficult to answer as wood decomposes easily, leaving behind little evidence of ancient wooden tools – especially in East Asia. However, a study published in the top journal Science on Friday suggests that wooden tools were widely used in southwest China 300,000 years ago.

These wooden tools, unearthed during excavations in 2015 and 2018, were the first ever found at a Palaeolithic – or early Stone Age – site in East Asia. The Palaeolithic age spans from around 2.5 million to 10,000 years ago.

Corresponding author Gao Xing, of the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told China News that the dozens of wooden artefacts unearthed at the Gantangqing site in Yunnan province represented a “world-class archaeological discovery”.

Gantangqing is situated at the southern edge of Fuxian Lake, near Yunnan’s provincial capital, Kunming. Excavations at the site uncovered many relics, earning Gantangqing a place among China’s top 10 archaeological discoveries in 2015.

“This discovery fills a gap in the study of Chinese Palaeolithic wooden tools,” said Liu Jianhui of the Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology in a paper in 2015. Liu is first author of the most recent study and led the second excavation at Gantangqing in 2018.

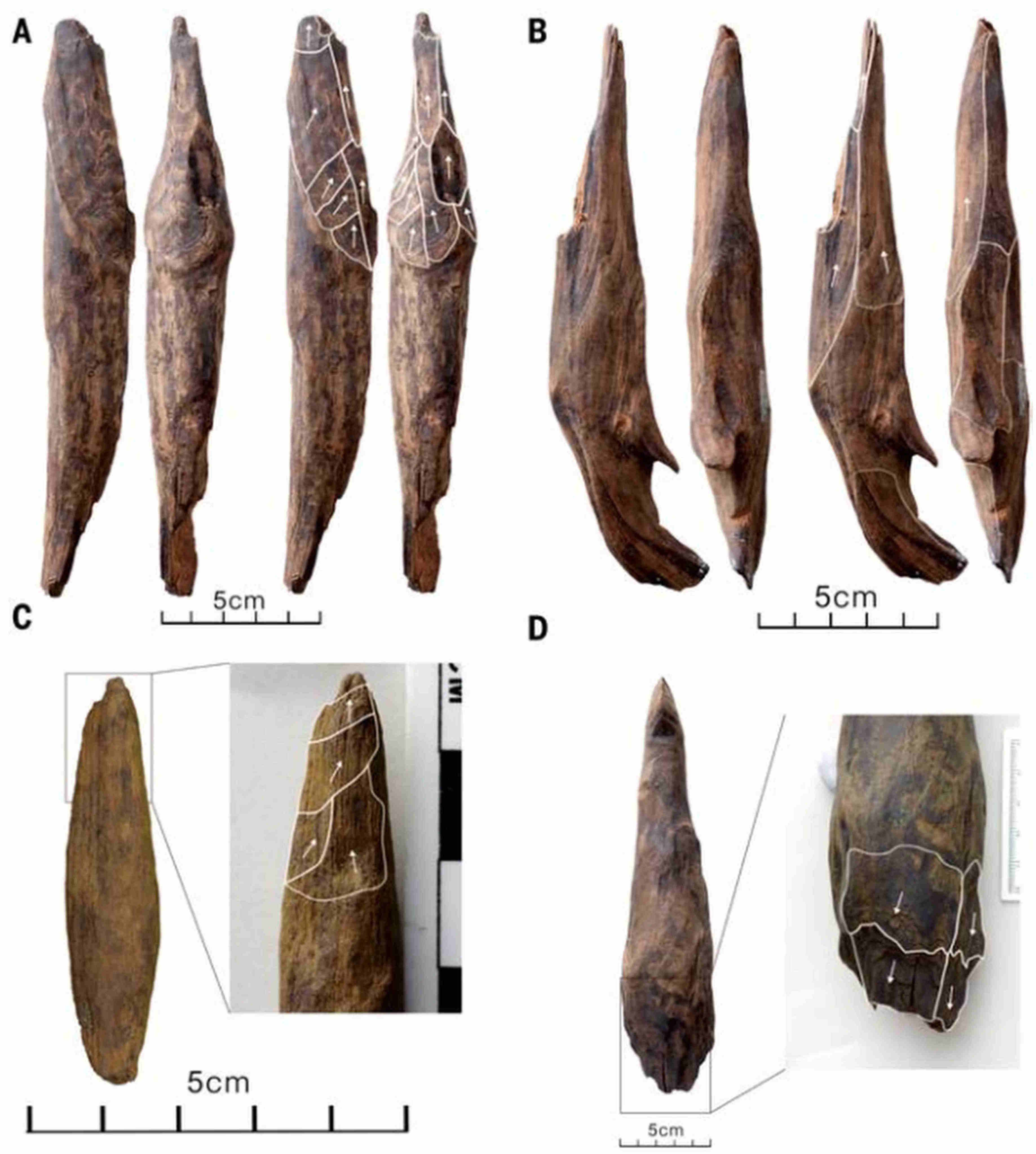

The site yielded nearly 1,000 wooden artefacts, including 35 tools that showed clear evidence of intentional shaping and use.

Evidence of wooden tools from the Early and Middle Pleistocene – a period from 2.58 million to 130,000 years ago – is scarce. Evidence of these tools had previously only been found in Africa and western Eurasia, with the most extensive collection before the Gantangqing discovery found in Schoeningen, Germany.

Compared to Schoeningen, the Gantangqing site featured a more diverse range of tools, especially small ones, particularly wooden tools used for plant collection and gathering.

The wooden implements unearthed at Gantangqing were predominantly for digging, while those found at the German site were mostly used for hunting, such as spears and throwing sticks.

Most of the tools found at the Gantangqing site were probably digging sticks used to access plant resources, according to the study. Residue analysis, which showed starch grains from tuber plants, suggested they were used for digging up aquatic plant rhizomes at ancient lake edges.

Most of the tools were made of pine, but a small percentage of the tools were made from harder wood. Scientific dating confirmed these tools were made around 361,000 to 250,000 years ago.

Four soft hammers were also discovered, representing the earliest known wooden hammers found in East Asia. One was in the form of a wooden stick, while the others were made of wood and deer antler fragments.

Some stone tools were also found at the site, but they were relatively simple, according to the study.

The scarcity of large stone raw materials might explain the presence of small and simple stone tools at the site, indicating that the inhabitants relied on wooden tools for collecting plants.

Gantangqing’s location near Fuxian Lake – the largest in Yunnan and the third-deepest lake in China – might explain how these wooden tools were able to be preserved.

The site features lake sediment deposits. Analysis of the rock layers showed that the lake’s water level fluctuated, causing early humans to migrate in response to these changes. Tools and fossilised plant and animal remains in the area were rapidly covered and buried.

A humid burial environment and deposits of fine clay particles shielded the artefacts from the air, preventing oxidation and preserving organic remains.

Liu noted that the sophistication of these wooden tools highlighted the importance of organic artefacts for understanding early human behaviour, especially in regions where stone tools alone suggested a less complex technological landscape.

The study was led by researchers from the Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the University of Wollongong in Australia.