By Owen Good

Price caps are often framed as a consumer protection measure – a way to stop touts profiteering and shield fans from exploitative pricing. At first glance, this approach appears to be a straightforward way to make live events more accessible and fair, ensuring that tickets are sold at a price deemed reasonable by policymakers. It is an argument that resonates emotionally, especially when fans are priced out of seeing their favourite artists or teams.

However, while well-meaning, this seemingly simple and fair solution actually obscures a host of deeper issues. In reality, price caps create unintended consequences – not just for the fans they aim to protect, but for the broader UK economy. When we move beyond the rhetoric and examine the practical impacts, it becomes clear that price caps, however well-intentioned, ultimately risk doing more harm than good.

Let’s start by examining the evidence: resale price caps can harm fans by pushing them out of safe, regulated marketplaces and onto riskier, unregulated platforms such as social media. Our research shows that 37 per cent of fans would likely turn to social media if they couldn’t access a regulated resale option – despite it being one of the riskiest places to buy tickets. In jurisdictions like Ireland and Victoria, Australia, where resale caps are in place, fraud rates are nearly four times higher than in the UK, according to research by Bradshaw Advisory. If mirrored here, that could drive the cost of fraud up from £340m to over £1.2bn. But there’s an additional, often overlooked consequence: the broader economic fallout. Resale markets don’t just help fans find and sell last-minute tickets; they underpin an ecosystem of spending that spans travel, hospitality, and retail.

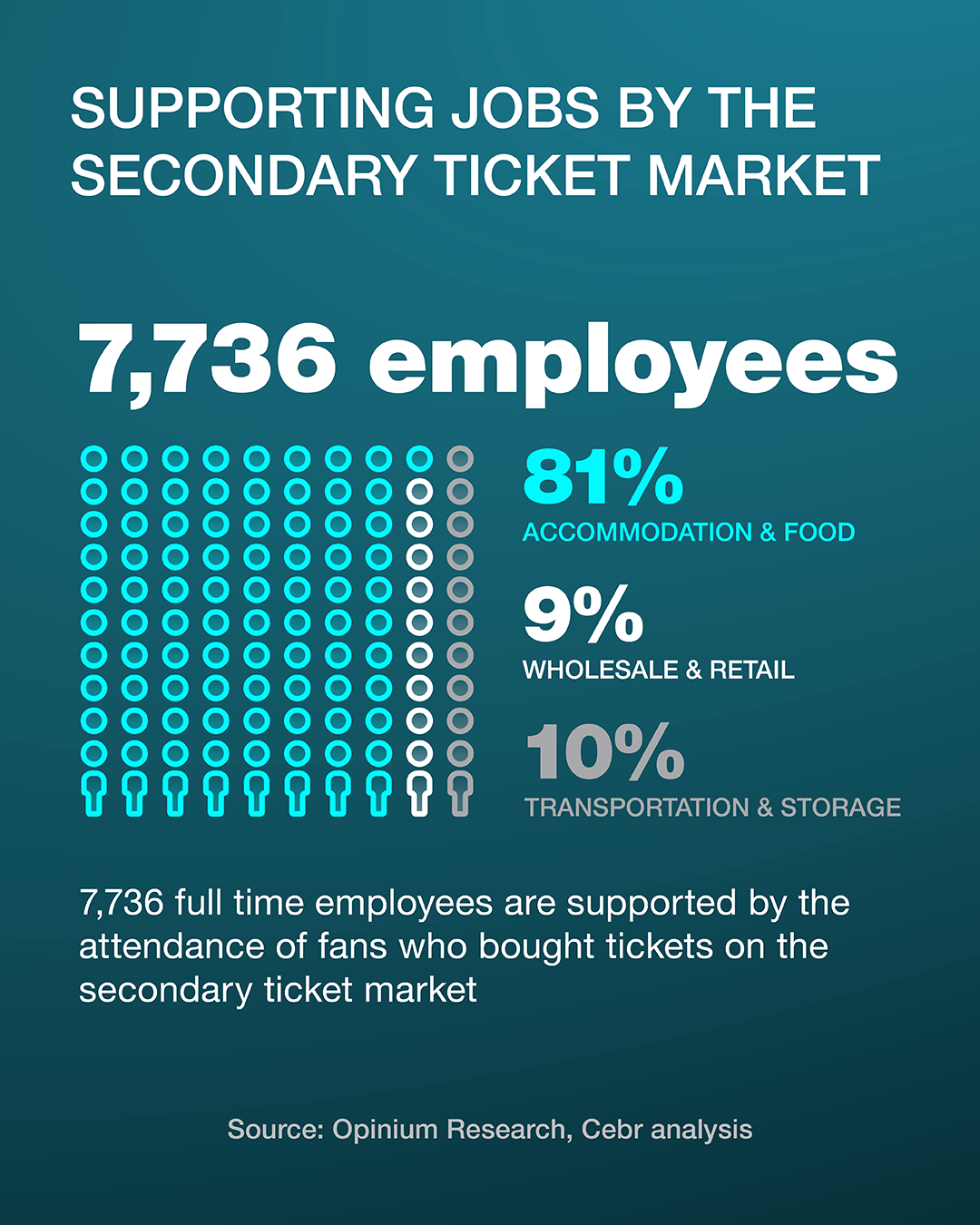

At the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr), we’ve analysed the data. When fans purchase resale tickets via secondary marketplaces, they spend an average of £629 on top of the ticket itself – on hotels, food, transport and merchandise. This secondary spending supports £733 million in annual turnover, contributes £270m to GDP, and sustains more than 7,700 jobs across the UK. If, as expected, price caps discourage reselling – for example, if fans who can no longer attend see no financial value in passing on their ticket – they may simply let their seats go unused. For every 1 per cent of tickets that go unused, the economy could lose approximately £7.3m in revenue. If just one in four tickets on the secondary market were to go unsold, this figure would rise to an estimated £183m.

Year after year, we continue to see the ticketing industry disappoint fans. Last year, the Oasis fiasco. This year, as recently as June 2025, thousands of NFL fans in Ireland were left empty-handed and frustrated after queuing for hours online for Pittsburgh Steelers versus Minnesota Vikings at Croke Park tickets. Strict price cap laws in Ireland mean there is no regulated, safe resale option if they missed out – no second chance to attend, no flexibility to pay what they feel the ticket is worth. Just two days after tickets went on sale, there is evidence of tickets being listed on social media platforms by individuals and suspected fraudulent companies. Desperate fans lured by posts for tickets that look too good to be true risk playing into the hands of the fraudsters who lie in wait.

So, who ends up out of pocket? The fans, certainly, but financial institutions are also on the hook to reimburse defrauded customers. Since October 2024, UK banks have been required to reimburse victims of Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud, which includes most ticket scams. With resale restrictions forcing more buyers onto risky channels, the financial burden is now spreading from fans to banks – and eventually to the wider economy. With sought-after tickets, fraudsters leverage both the fear of missing out on a unique opportunity and a sense of urgency due to scarcity and high demand. Several financial institutions see social media fraud spike around popular live events – and some have voiced their opposition to price caps. Revolut saw ticket scams increase by 40 per cent in the run-up to Taylor Swift concerts in London in August 2024. The fintech giant has publicly shared its position: banning or capping resale doesn’t stop these scams; it simply provides another platform for them to thrive, costing fans and the wider economy through increased fraud. Ultimately, not only do fans suffer unintended consequences, the economy loses.

Yes, we must protect consumers. But price caps – while well-intentioned – are a misguided solution. Anyone familiar with the dynamics of supply and demand understands that capping resale prices will only re-route the fan demand off trusted platforms and into unregulated corners of the internet, where fraud is rife. With its proposed legislation, the UK government risks doing more harm than good – exposing consumers to greater danger and undermining a sector that sustains thousands of jobs and generates millions in economic value. The alternative isn’t price control, it’s regulation that works. That means transparency, enforcement of existing rules, and ensuring that safe, well-regulated resale platforms remain viable – and continue to contribute to the UK economy.

Sponsored by Viagogo