By Elina Noor

A day before the controversial military parade in Washington celebrating the US Army’s 250th anniversary (which, coincidentally, fell on President Donald Trump’s 79th birthday), a more discreet yet significant event took place. On June 13, the US Army swore four C-suite technologists into its reserve ranks with the launch of Detachment 201, its executive innovation corps.

The newly commissioned lieutenant colonels are Shyam Sankar, Palantir Technologies’ chief technology officer; Andrew Bosworth, Meta’s chief technology officer; Kevin Weil, OpenAI’s chief product officer; and Bob McGrew, Thinking Machines Lab’s adviser and formerly OpenAI’s chief research officer.

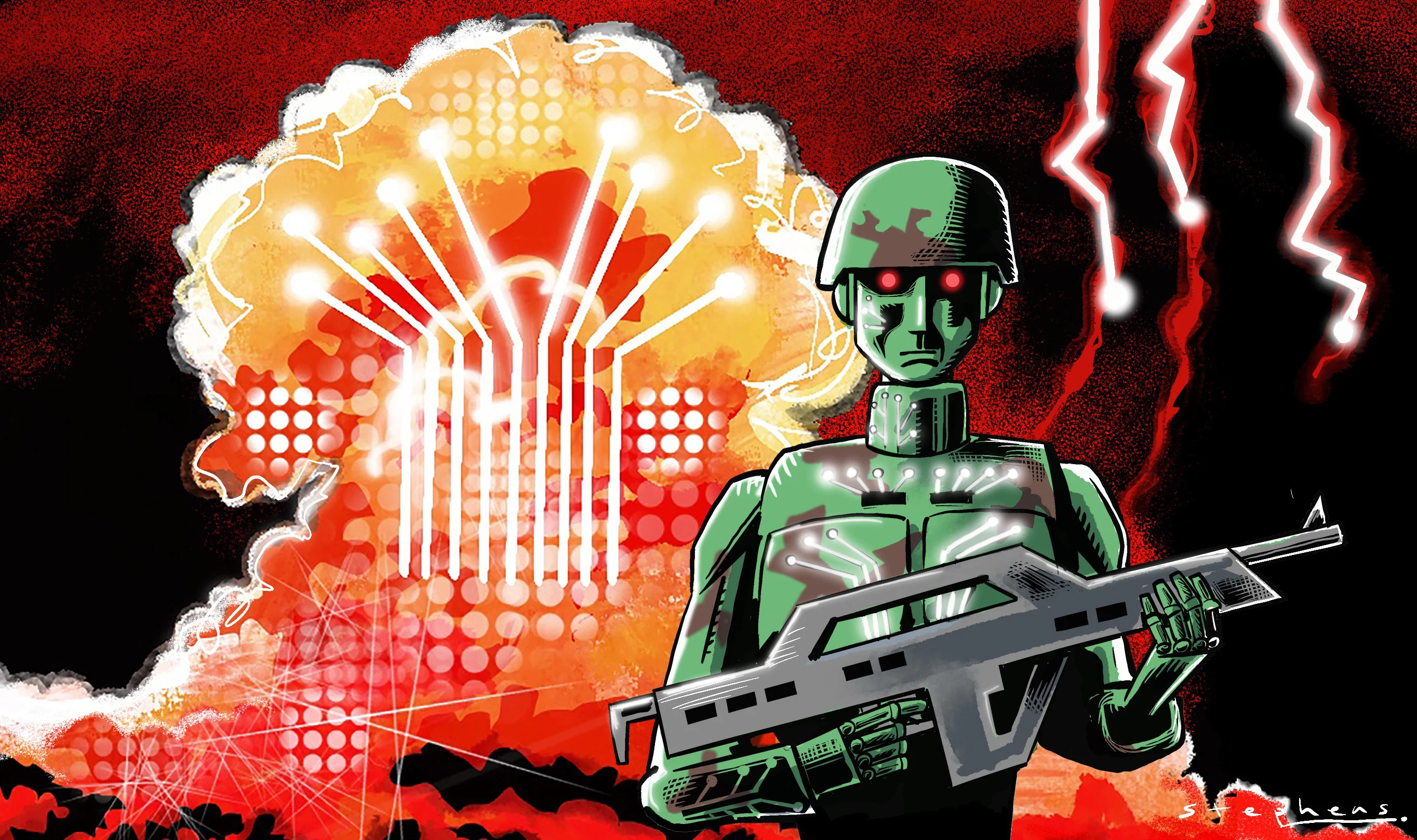

Dressed in military fatigues at their oath-taking ceremony, the reserve officers symbolised a fusion of two of the greatest US exports: capitalism and lethality. This merger of the boardroom and the battlefield is not new. In the early 1960s, Dwight Eisenhower cautioned against the rise of the US military-industrial complex even as he recognised the “imperative need” for it.

Since then, US tech dominance – led by the private sector and supported by the government – has only accelerated the inevitability of the military-technology complex in the digital age.

But Silicon Valley’s attitude towards Washington was not always this eager. The image of libertarian tech elites in the West Coast in the early days of start-ups, along with their ideals of individual autonomy and limited government, is a far cry from the assertive nationalism of US Big Tech now.

Alex Karp, CEO of Palantir, a major US defence and security contractor that specialises in commercial data analytics software, has unapologetically championed Western dominance through a combination of hard power and technology. Contemptuous of protests by tech workers against engineering technology for US weapons development, Karp has instead embraced the idea of scaring America’s enemies and killing them, if necessary.

He and his chief technology officer Sankar believe Silicon Valley’s successful technologists owe “a debt to the American people and to the free and liberal society that supports us”. In Sankar’s case, serving in the military repays the American dream that gave his immigrant father and him a life.

But a large part of this shift in Big Tech’s attitude has also been driven by opportunism. Sankar has openly railed against the lethargy of legacy defence contractors, advocating instead for Silicon Valley’s agility – some would say, recklessness – to move fast and break things in an age where “the West has empirically lost deterrence”.

OpenAI, threatened by rival Chinese developments such as DeepSeek and Zhipu AI, has seized the geopolitical opening to advance “democratic AI around the world” and ensure “American-led AI prevails” over Chinese Communist Party-led artificial intelligence.

Last year, OpenAI partnered with defence start-up Anduril to integrate AI into US defence systems. The companies’ media statement pledged to ensure US technological leadership against “adversaries who don’t share our commitment to freedom and democracy”. To ChatGPT users outside the United States, it reads in awkward juxtaposition against OpenAI’s charter to “act in the best interests of humanity”.

OpenAI’s bet is paying off. A few days after the announcement of Detachment 201, the defence department awarded OpenAI a US$200 million contract to develop advanced AI capabilities for national security challenges. Google, which previously pledged not to design or deploy AI for weaponry, surveillance or other technologies that harm, injure or contravene international law and human rights, is now another contender for more work in the lucrative defence sector, having recently and quietly shed its self-restraint.

Likewise, Meta has made its Llama language models available to the US government as well as to companies such as Lockheed Martin, Microsoft, Anduril, IBM and Palantir for defence and security uses. This is despite Meta’s injunction against the use of its models for “military, warfare, nuclear industries or applications”, among others.

As Meta and its peers make clear, their companies are US-born and bred. Their success, they say, was built on the entrepreneurial ecosystem and democratic values the US ostensibly upholds. To these companies, advancing US primacy in AI and its geopolitical interests produces a virtuous trickle-down effect for the rest of the world, premised on the responsible and ethical use of tech.

But as many in the rest of the world know all too well, this narrative of US tech munificence – like the AI models coming out of Silicon Valley – is a biased distortion of reality. First, it assumes US values are universally translatable or beneficial. Second, it ignores the exploitative data, labour and environmental practices in many countries that have sharpened the efficacy of AI tools.

For a reality check on the first point, just ask communities in Myanmar and India that have experienced terrifying violence courtesy of Facebook’s algorithms and surveillance-based business model. For a fact check on the second, it’s worth remembering that OpenAI outsourced the tedium and toxicity of data labelling for ChatGPT to workers in Kenya, Uganda and India for less than US$2 an hour. OpenAI’s partner was San Francisco-based Sama, which billed itself as an ethical AI company.

As the distinction between US tech and the state becomes increasingly blurred and as moguls like Karp invoke an Oppenheimer moment for AI in its strategic potential to advance America’s raw power, Asia will recall the horrors of nuclear devastation, delivered by the unforgiving lethality of B-29 bombers. Left unchecked, Silicon Valley’s inspiration for the future of the West could well be a nightmare for the rest.