By News18

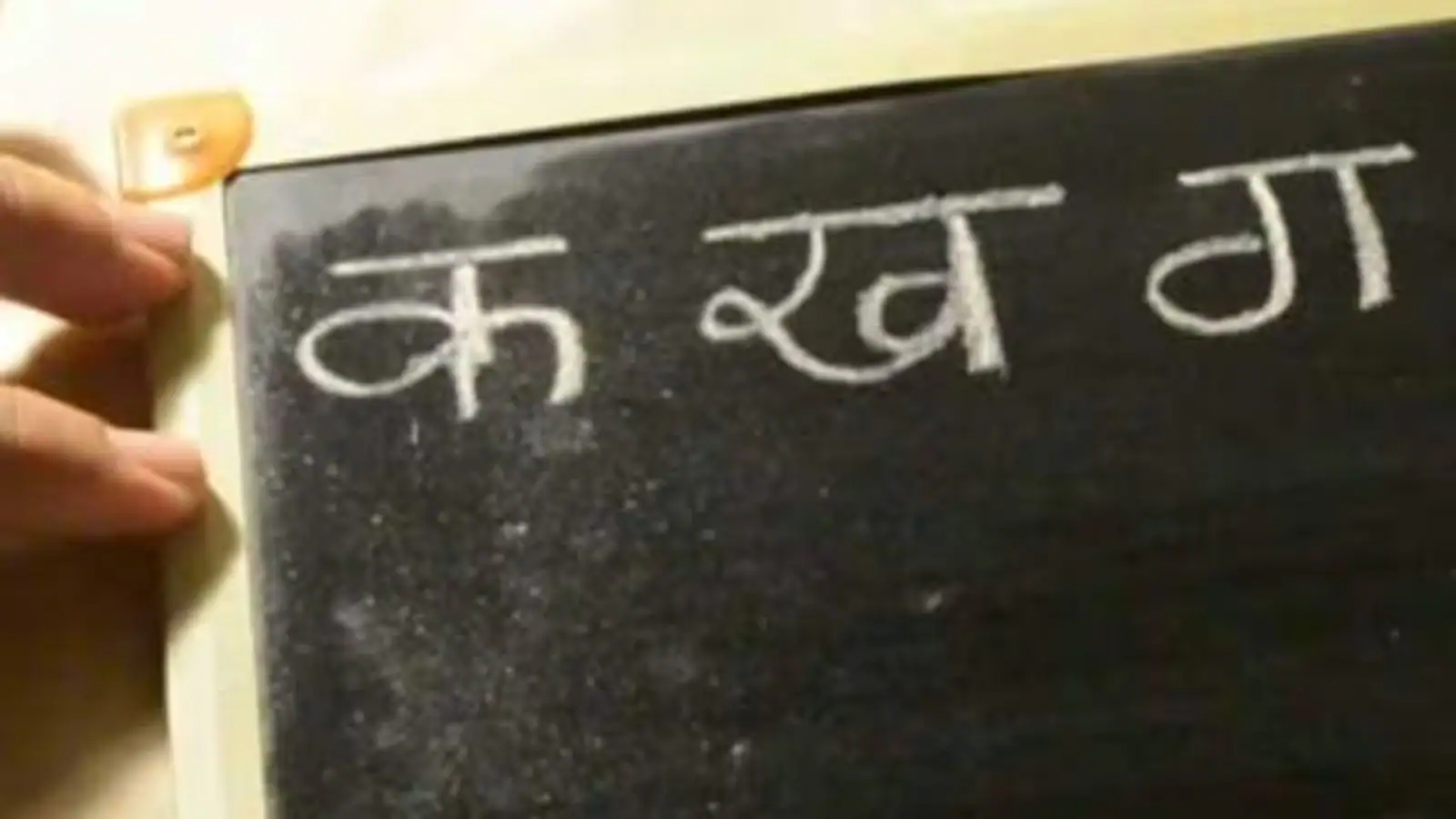

In a country as linguistically diverse as India, the question of language is not just about communication; it’s about identity, culture, and power. While Hindi is often presumed to the Rashtrabhasha (national language), the fact is, it never officially became one. Instead, Hindi holds the constitutional status of Rajbhasha (official language), a crucial but fundamentally different designation.

This distinction, though seemingly technical, lies at the heart of a long-standing debate that has influenced education policy, inter-state politics, and even shaped the federal structure of the country. And the issue resurfaced recently when the Maharashtra government was forced to withdraw its decision to make Hindi a compulsory third language in government schools after a surge of protests, the first major backlash against Hindi in the state in recent memory.

What Is Official Language?

An official language is one that is used for governmental functioning – administrative communication, drafting of laws, office work, and public services. In India, Hindi in the Devanagari script was adopted as the official language of the Union under Article 343 of the Constitution, to be used for central government communication. English was allowed to continue temporarily but, owing to political compromise and practical necessity, it continues as an associate official language even today.

The purpose of an official language is functional; to streamline governance and communication. States are free to choose their own official languages as per the Constitution, and many do – from Tamil in Tamil Nadu to Marathi in Maharashtra to Assamese in Assam.

What Is National Language?

A national language, by contrast, serves a symbolic purpose. It typically represents a country’s cultural identity, unity, and historical continuity. A national language is seen as a unifying thread – often the most spoken or widely understood tongue – and may be used in education, cultural messaging, and national events. But crucially, India has no national language. The Constitution does not declare any language, not even Hindi, as the national language.

This was a conscious choice made during the drafting of the Constitution. When the idea of making Hindi the national language was debated in the Constituent Assembly, it encountered stiff resistance, particularly from representatives of South India and the northeast, who feared the dominance of Hindi would marginalise their native languages and cultural identities.

Why Hindi Didn’t Become The National Language

Although Hindi is spoken by over 40% of Indians and is the most widely used language in the country, it could never be elevated to the status of national language due to the country’s federal and multicultural character. Language movements across states made it clear: a single national language would not reflect India’s pluralism.

In the 1950s and 60s, violent protests erupted in Tamil Nadu when the Centre attempted to make Hindi the sole official language. The anti-Hindi agitation became a pivotal moment in politics, influencing language policy and prompting the government to retain English alongside Hindi. Similar tensions emerged in Assam, Punjab, and parts of Maharashtra, where regional languages served as the bedrock of identity.

Dr Ram Manohar Lohia’s “Angrezi Hatao, Hindi Lao” campaign in the same period did receive significant support in Hindi-speaking regions, but it could never generate national consensus. Over time, the movement to remove English lost momentum, and the campaign to impose Hindi faded as India’s linguistic realities became too complex to ignore.

Legal And Constitutional Position

Legally, Hindi is the official language of the Union government, not of the country as a whole. The Constitution provides for 22 scheduled languages, and every state has the liberty to choose the language(s) for its administration and education. Even if Hindi were to be declared the national language today, it would not bind the states to implement it unless accompanied by a constitutional amendment – which, given the political sensitivities, remains highly unlikely.

India’s position is not unique. Many multilingual countries refrain from naming a single national language:

Nepal recognises Nepali as the official language, not national.

Bhutan uses Dzongkha officially but doesn’t declare it a national language.

Sri Lanka has two official languages – Sinhala and Tamil – but language differences were at the heart of decades of civil war.

Canada officially recognises both English and French, but linguistic battles in Quebec have led to decades of cultural and legal disputes.

Belgium remains divided between Dutch-speaking Flanders and French-speaking Wallonia, with both having official language rights.

China has Mandarin as the official language but faces internal dissent from speakers of Uyghur, Tibetan, and Mongolian.

These global parallels show how language, when politicised, can lead to division rather than unity.

The Maharashtra Language Row

The recent controversy in Maharashtra serves as a fresh reminder of these unresolved tensions. The state government’s announcement to make Hindi a compulsory third language in schools triggered widespread protests across political and linguistic lines. Although Hindi has not traditionally faced resistance in Maharashtra, this move was seen as a top-down imposition, especially in a state where Marathi holds strong cultural significance.

Sensing the growing backlash, the government was quick to roll back the decision. While officials framed it as a policy reconsideration, it was, in effect, a retreat in the face of public dissent.