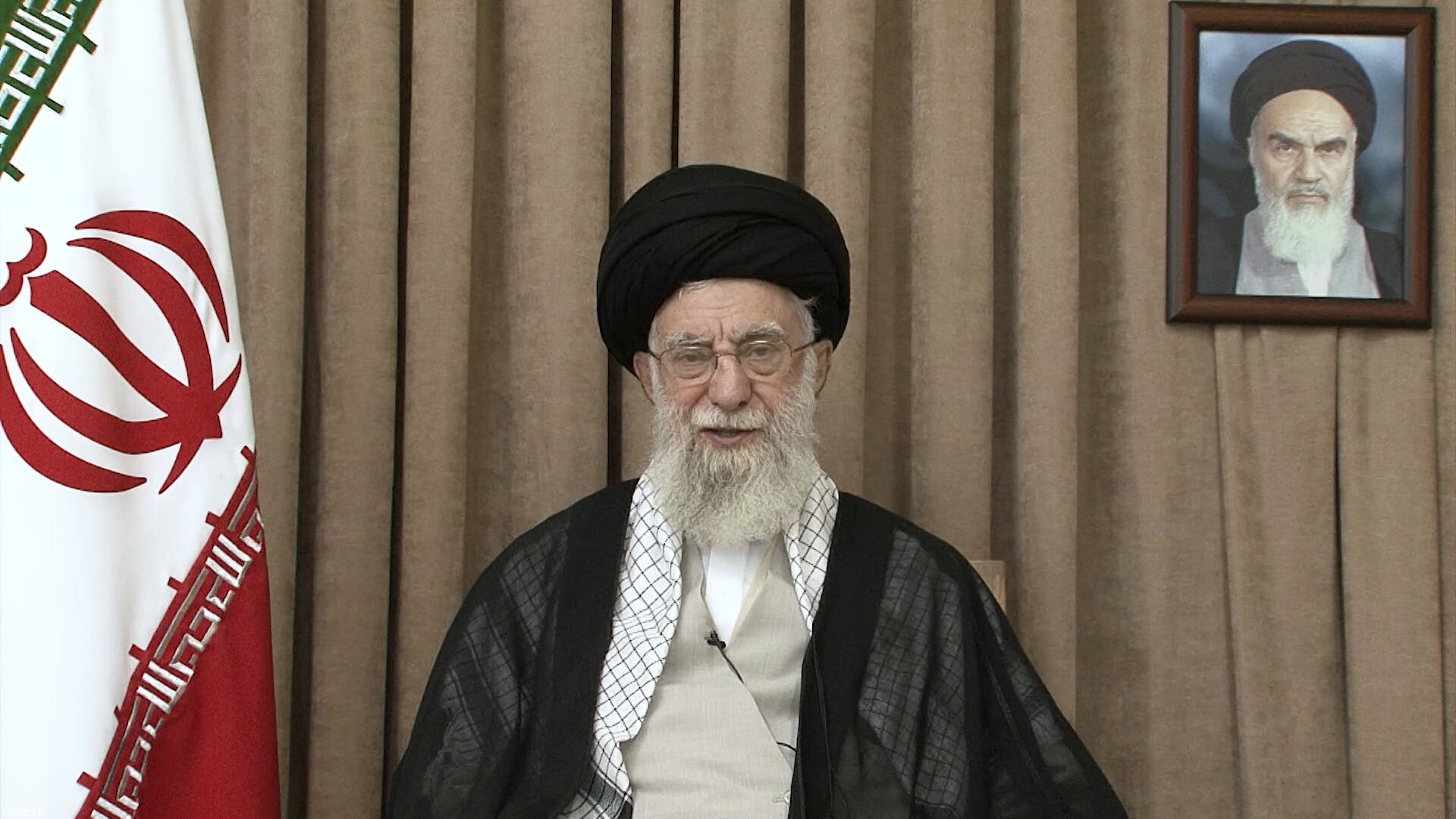

By Tom O’connor

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has evaded threats of assassination and regime change as the ceasefire declared by President Donald Trump halts the “12-Day War” that saw the Islamic Republic face an unprecedented assault from Israel and direct U.S. intervention.But as the 86-year-old cleric emerges triumphant from the bout鈥攄eclaring victory in his first post-truce remarks last week with Tehran still reeling from the Israeli air campaign鈥攖he very prospect of his downfall has accelerated discussions about his potential successor, and even given rise to speculation of a major shake-up in future governance.And while a largely fractured array of Iranian dissidents abroad calls for a popular uprising to dismantle the Islamic Republic altogether, little evidence suggests such a development is imminent. Rather, analysts with sources on the ground tell Newsweek that if change does come in Iran, it’s most likely to emerge from within, and from those with established influence.This debate plays out amid shifts already taking place in the balance of power in Iran, home to a unique variety of political factions鈥攁 clerical ruling class and a duality of military power divided between the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the conventional armed forces, the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, also known as the Artesh.The IRGC has substantially consolidated political power and influence in the decades since its establishment at the dawn of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that brought Khamenei’s predecessor, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to power. Some observers believe the rise of these elite forces may even eclipse that of the next supreme leader despite their sworn loyalty to the office.Meanwhile, the Artesh, heirs to the pre-revolutionary Iranian Army commanded by the ousted monarchy, have long been superseded by the IRGC in key respects. Others feel this may be changing, especially in the wake of major leadership losses suffered in the battle with Israel and a growing Artesh presence in top positions.In any case, “Khamenei’s position is surely weakened,” Arash Azizi, fellow at Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, told Newsweek.A Revolutionaries’ RevolutionAzizi recently penned an article for The Atlantic in which he cited several unnamed Iranians testifying to an insider plot to sideline Khamenei amid the war with Israel. The original plan, according to the sources cited by Azizi, was to effectively supplant the supreme leader’s authority with a high-ranking leadership committee that would negotiate an end to the conflict.The Iran-Israel war appears to have since ended for now, with Khamenei still in power. Yet Azizi argued that the fallout has only “heightened power struggle over his succession,” though “it’s still not clear who will come on top.””The leading factions are based in the military and business elites. The plots in Tehran for a post-Khamenei Iran include a cross-section of these elites,” he added. “Some are more trigger-happy than Khamenei ever was. But none of the serious contending factions for power share Khamenei’s old-school ideology. They act out of self-interest and military rationale not doctrine.”Among the top contenders for consolidating power is the IRGC, which Azizi said was “hit badly but it’s far from destroyed” after the war with Israel.The IRGC’s network extends past Iran’s borders. Already overseeing the powerful Basij paramilitary force tasked with maintaining internal order, the IRGC has also been a central driver of Iran’s Axis of Resistance coalition, which, though battered from a 20-month war with Israel preceding the latest conflict, counts members in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Yemen and beyond.The IRGC also commands clout beyond the military realm. The IRGC has expanded its holdings at home, cultivating growing influence over the Iranian economy and other institutions that further entrench its position within the country.”You can’t decapitate a massive force with 190,000 members and a financial empire which controls up to half of Iran’s economy,” Azizi said. “So, I don’t see it as particularly battered or beleaguered. But the IRGC has never been a unified institution. It includes different factions, each of which will try for jockey power in the post-Khamenei era.”Ali Alfoneh, senior fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, also viewed the IRGC as steadily rising to the helm in Iran.”The clerical establishment’s political authority has been in decline for years, driven by a structural shift in the balance of power between the clergy and the IRGC,” Alfoneh told Newsweek. “Faced with mounting domestic demands for political, economic, and social reform鈥攄emands the regime proved either unwilling or unable to meet鈥攁longside persistent external threats, Khamenei increasingly delegated the management of both internal repression and external defense to the IRGC.””This reliance has come at a price: significant economic concessions and growing IRGC influence over strategic decision-making, which has eroded the historical division of labor between clerical governance and military guardianship,” he added.Moreover, Alfoneh argued that the setbacks of the recent conflict may ultimately compel an already empowered IRGC to lay blame on political and religious decision-makers, a trend he said has been established in Iran since the devastating war fought with Iraq in the 1980s.”Since the end of the Iran-Iraq War, IRGC commanders have consistently accused the clerical leadership of betrayal,” Alfoneh said. “A similar narrative is likely to re-emerge, with IRGC figures accusing the civilian leadership of forfeiting Iran’s nuclear capabilities at the negotiating table and blaming the clerical establishment for Iran’s systemic dysfunctions.””The general public, already loathing the clerical regime, may momentarily overlook the IRGC’s complicity in those very failures,” he added.The Nationalists and the PragmatistsAs for the Artesh, Alfoneh felt the political role of the long-overlooked conventional forces would “remain marginal.”But Kamran Bokhari, senior director at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy in Washington, D.C., argued that the Artesh was actually the force to watch out for as Iran’s internal dynamics shift.”I think what will happen is the reverse,” Bokhari said. “The Artesh is going to use Khamenei, is going to use public sentiment, is going to use the people who’ve been sidelined, the more pragmatic conservatives and the reformists, to build a coalition.”Citing conversations with those inside the country, Bokhari said that Khamenei, “overwhelmed” by the influence of the IRGC, had already “started to rely on the Artesh as well, bringing them into the equation” in order to maintain control.Among the few public indications of the Artesh assuming a greater role include the choice of Major General Abdolrahim Mousavi, former Artesh commander-in-chief, to replace Iranian Armed Forces Chief of Staff Major General Mohammed Bagheri, who was one of many leading IRGC figures slain during Israel’s opening salvo against Iran.Mousavi was replaced by Major General Amir Hatami, who was previously named in 2017 as Iran’s first defense minister attached to the Artesh as opposed to the IRGC since 1989. Iran’s current defense minister, Major General Aziz Nasirzadeh, named in August by reformist President Masoud Pezeshkian, also has an Artesh background.But Bokhari emphasized that the IRGC and clerical elite could not be completely routed. Rather, he said, the coalition led by the Artesh would also need to ally with “more pragmatic elements of the IRGC” as well as “more pragmatic clerics” to reshape the country.Bokhari drew a comparison to the 2017 power play conducted by Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, through which the young, rising heir apparent ordered a sudden, sweeping wave of arrests targeting a number of influential inside players he tied to corruption and fundamentalist interpretations of Salafi Wahabism.Crown Prince Mohammed has since embarked on a nationwide transformation, embracing a more nationalist path for a monarchy whose authority has long been largely rooted in religious legitimacy and tribal power structures. At the same time, he has maintained the absolute rule of the House of Saud.A looming change in Iran may be even more radical than what’s taking place in Riyadh, entailing a reinterpretation of the decades-old Veleyat-e-Faqih, or “Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist” system, through which Khamenei has the final say in all affairs. Revered by his followers as a marja’, a leading Shiite Muslim cleric, his role or that of his successor may come to resemble others holding this religious title, such as Iraq’s Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, who holds no government position yet retains vast influence.Like Alfoneh, Bokhari has observed a gradual, yet steady process of transformation taking place from within Iran, largely independent of U.S. and Israeli designs, even if recent events may accelerate it. He calls it “internal evolutionary regime change.””This is going to be regime evolution, depending on the pace,” Bokhari said. “What you’re going to see is maybe the Islamism is going to die out over time, but what the Iranian regime and the Artesh and the officers and everybody in the elite won’t do is they can’t stop being Iranian nationalists, and there’s going to be some level of religion informing, indirectly, their political identity and their policies as well. But they have to become pragmatic.”Pragmatism already appears to be prevailing over principlist positions in the political sphere, as evidenced by Pezeshkian’s election last year and subsequent pursuit of nuclear talks with Trump’s administration despite Khamenei’s initial indications of refusal.Pezeshkian bested an array of mostly hard-liner candidates to become Iran’s first reformist head of government since former President Hassan Rouhani. Rouhani led from 2013 to 2021, pioneering the initial nuclear agreement with the United States, and was succeeded by President Ebrahim Raisi, a conservative with close ties to Khamenei and once considered a front-runner for next supreme leader until his death in a May 2024 helicopter crash.Rouhani also appears to be gradually reclaiming the spotlight, despite having being barred last year from candidacy to the Assembly of Experts, the 88-member body of clerics tasked with choosing Khamenei’s successor. The former president issued a statement following the Iran-Israel ceasefire last week urging that, “this crisis must create an agenda for correcting our course and rebuilding the foundations of governance.”While it remains to be seen how the positions of Pezeshkian, Rouhani and like-minded figures will be affected once Khamenei’s 36-year tenure comes to an end, London-based outlet Amwaj.media recently reported that orders have already been given to the Assembly of Experts to begin the process, citing insider sources.”It is too early to assess the specific impacts of the current conflict on leadership transition in Iran, but there are indications that the inevitable process of replacing 86-year-old Khamenei may be accelerated given the need for cogent and authoritative leadership,” Amwaj.media editor Mohammed Ali Shabani told Newsweek.”In this respect, there are speculations that Khamenei has already delegated some authority, but this is actually a process that was initiated in recent years,” he added. “As such, the war with Israel is not the sole factor that has brought about this reported trajectory.”The Resilient RepublicFor now, plotters remain in the shadows. Even in the face of the nation’s most serious conflict since its war with Iraq, Khamenei signals little concern about his position, and overt signs of unrest remain scarce.Similarly, any dissonance in the IRGC-Artesh equilibrium has yet to disrupt Iran’s public display of unity.”While the new Chief of Staff of the Iranian Armed Forces has an Artesh pedigree, unlike his IRGC predecessor, all of the fallen IRGC commanders seem to have been promptly replaced,” Shabani said. “This indicates that the Iranian state, including the military, is highly institutionalized, which goes back to the question of how and whether short-term changes in personnel may shift longer-term trajectories, such as military-clergy-state relations鈥攏ot to mention foreign policy.””The Islamic Republic is a large machine with many cogs,” he added.Analysts have long attested to the resilience of the Islamic Republic in the face of external threats. One former senior Israeli official who told Newsweek amid the conflict that Israel may be actively fostering contacts within the Artesh also noted that Iranians were unlikely to make any moves that could be interpreted as siding with the enemy in wartime.Mostafa Najafi, Iranian researcher who specializes in Middle East conflicts and Iranian foreign policy, acknowledged that some within the country may seek to try their hand at taking advantage of the current situation to push their agendas, though he argued that a united front remained the core takeaway from the ordeal.”Domestically, some political factions may attempt to leverage the post-war environment to promote reforms, policy changes, or recalibrate institutional roles,” Najafi told Newsweek. “However, from the broader perspective of the state, the priority remains on national unity, rebuilding capacities, and reinforcing strategic security and political doctrines in the face of external aggression.”In this respect, Najafi argued that any reforms set to be taken would ultimately uphold the central tenets of the Islamic Republic.”Any changes or transformations within Iran’s political system occur strictly within constitutional frameworks, preserving the core principles of the Islamic Revolution and the country’s independence,” Najafi said.These principles also extended to the IRGC and the Artesh, as “while these two military institutions differ in certain respects, they remain aligned on one crucial matter: defending Iran,” he argued.”Overall, the Islamic Republic demonstrated during this 12-day war that it possesses the institutional and strategic capacities to navigate crises,” Najafi said. “Whether in leadership succession or military restructuring, what remains evident is the prioritization of stability, authority, and strategic rationality when confronting threats.”