In the searing heat of the Outback sun, 15-year-old Jacinta ‘Cindy’ Rose Smith lay dying on the side of the Mitchell Highway.

Her young body ravaged by massive internal injuries, Cindy’s final moments unfolded in the dust of a remote stretch of road near Bourke, in northwestern NSW, in 1987.

Hours earlier, Cindy and her cousin Mona Smith, 16, had accepted a lift from white sexual predator Alexander Ian Grant in his Toyota HiLux ute.

He was drunk – they crashed. What happened next is almost too horrific to put into words. Rather than help the stricken Indigenous girls, Grant – who escaped the crash uninjured – violated Cindy as she lay fatally injured.

But the horror was not over.

The lecherous excavator driver, using a top-flight Sydney barrister, went on to evade blame and fled justice by using a loophole in the law.

Now, almost 38 years later, the loophole will be closed as Cindy’s Law is set to be enshrined in NSW parliament to prevent sexual predators from evading prosecution because of uncertainty over the timing of their victim’s death.

The name of the law has been chosen by the families of Cindy and Mona, both of whom died as a result of Grant’s drunk driving when he crashed and rolled his ute near Enngonia that December night.

It is the latest chapter in a case that has spanned decades and laid bare the racism at Australia’s heart, leading to tears among law enforcement and the judiciary as they reviewed the harrowing, decades-old evidence.

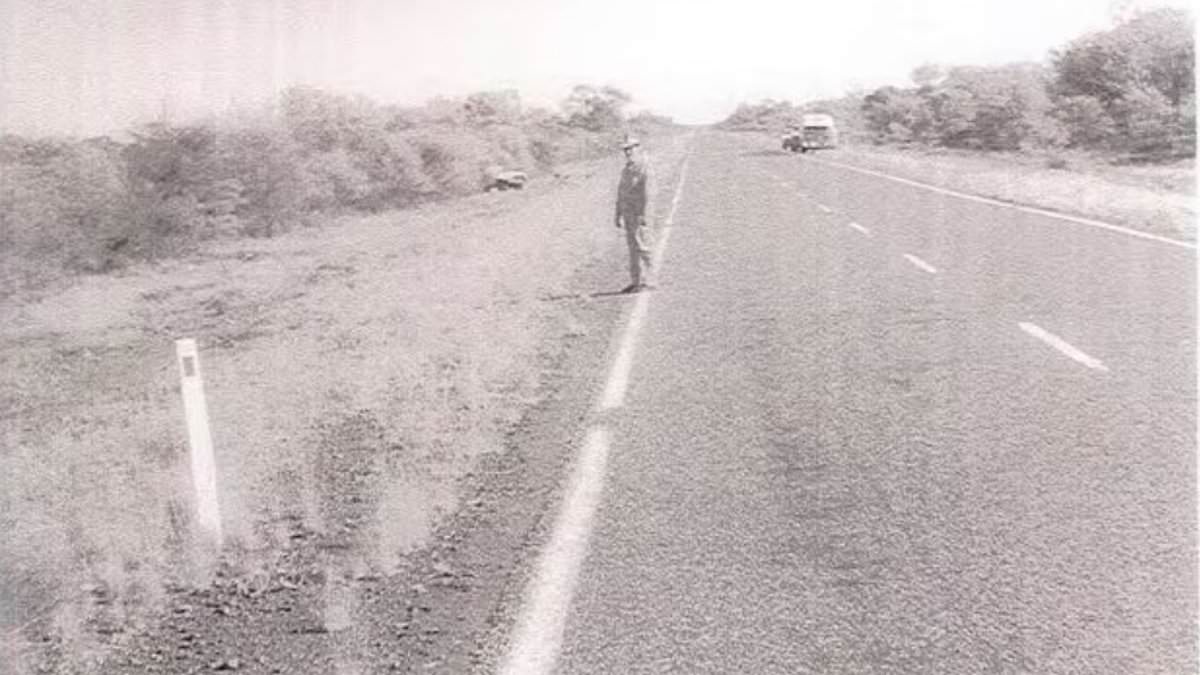

On that early morning on the remote stretch of highway, an uninjured Grant was discovered at the crash site, still drunk and dishevelled, but the crash’s only survivor.

Police found Grant with his arm slung across the body of Cindy, who was nearly naked and exposed on a tarpaulin.

In contrast to the scene observed by the first witness to the crash site, Cindy had been moved, her legs positioned to expose her genitals, and her clothing disturbed before or during her death.

Police charged Grant with dangerous driving causing the cousins’ deaths, but another charge of sexually interfering with Cindy’s corpse was withdrawn.

The controversial ‘no-billing’ of the charge before Grant’s 1990 trial was due to a legal technicality: it was not known if Cindy was dying from unsurvivable injuries as he molested her, or whether she was already dead.

Last year, an inquest into Cindy and Mona’s deaths erupted in emotional scenes as a coroner ruled that Grant had molested a deceased Cindy on the Enngonia Road, 850km northwest of Sydney.

State Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan found that Grant had engaged in ‘predatory and disgraceful conduct’ with Cindy on the side of the highway after she died 63km outside the girls’ home town of Bourke.

The coroner also found that Grant had previously driven around Bourke looking for young Aboriginal girls to get drunk and sexually assault.

‘Horrifyingly, the evidence indicates he sexually interfered with Cindy after she had passed,’ the coroner told the inquest.

‘I am satisfied there was some sort of sexual interference of Cindy by touching Cindy’s breast or genital area after she had passed.’

Ms O’Sullivan was also satisfied that Grant had remained in the vehicle as it rolled, but that Cindy and Mona Lisa had been flung from the ute and sustained catastrophic injuries when it ‘rolled onto them’.

She could not estimate the specific time of their death, but said they died ‘very soon’ after the accident.

‘Mona… from multiple internal injuries including head and lung injuries and extensive blood loss. Cindy… from multiple internal injuries including pelvic and lung injuries and extensive blood loss.’

During the inquest, former police officers, including one veteran policeman, broke down in tears.

The inquiry ended on a heart-wrenching note as Mona Lisa’s mother, June, performed a haunting song dedicated to her daughter, My Heart is Broken, to a captivated courtroom of judicial officers, police and family.

Now that Cindy’s Law will be passed to address the legal loophole, the Smith cousins’ families have welcomed the long-overdue legal reform.

‘It is 37 years now. All the time I’d think about it, no justice, no one [held] accountable,’ Jacinta’s mother, Dawn Smith told The Australian. She said that despite Cindy’s Law being a long time coming, it was important and ‘it might help other families’.

Coroner O’Sullivan also found last year that Grant had lied to police when he changed his story and claimed that Mona had been driving the ute when it crashed.

This allowed him to wriggle out from under the dangerous driving charges, leading to his acquittal at Bourke court in 1990 by an all-white jury.

Inside the courthouse in 1990, a disgusted Dawn Smith hurled her shoe at the jury. Grant fled town, but never spent a day in prison and lived the rest of his life in obscurity until he died, aged about 70, at a NSW nursing home in 2017.

Ms O’Sullivan concluded that detective work on Mona and Cindy’s death had been ‘inexplicably deficient’.

She said ‘tensions’ between police and the Aboriginal community and ‘the existence of racial bias within the NSW Police force at the time’ impacted the investigation.

Ms O’Sullivan also found it unconscionable that Cindy and Mona Lisa’s mothers, Dawn and June Smith, found out about their daughters’ deaths ‘from other family members rather than being advised by police’.

The police forensic sweep of the crash scene was so inadequate that when family members took themselves to the location on the Mitchell Highway, they found Mona Lisa’s partially torn-off ear in the dirt by the road.

‘This inquest was their final hope to obtain answers about the circumstances of the deaths of their beloved girls, some form of justice, although decades late,’ the coroner said.

‘They were loved dearly by their families. They attended Bourke High School where they were clearly popular… they were inseparable, like sisters.

‘Mona and Cindy were young bright girls sparkling with life and excitement, they had big hopes… and dreams.

‘The grief and anguish of their passing remains raw for their families.’

The NSW government said in a statement that Cindy’s Law was ‘in direct response to an issue raised in the coronial inquest into the tragic deaths of Mona Lisa and Jacinta Rose ‘Cindy’ Smith and the tireless advocacy of their families for reform.

‘The penalty for indecently assaulting a deceased person will also be increased’.