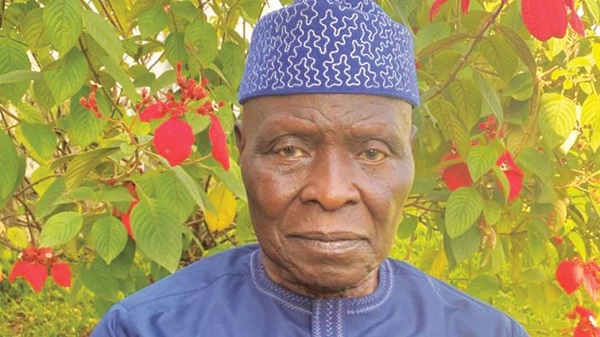

He was a man of many parts in a historic journey of over eight decades – a good teacher, an astute administrator, a progressive politician, a principled pro-democracy activist, a trustworthy community leader, and an elder statesman.

Cornelius Olatunji Adebayo, former governor of Kwara State on the platform of the defunct Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) and chieftain of National Democratic Coalition (NADECO) has bowed out after illness. He was 84.

The consensus about him is that he was a gentleman and a refined politician who could not levy partisan war; he was a man of honour and integrity.

Adebayo died a fulfilled man, having made his mark in teaching, his chosen profession, and politics, his vocation. He was a teacher at the University of Ife, now Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), before he returned to the Northwestern State to serve as Information Commissioner. In 1983, he was kicked out of the Kwara State House by the coup plotters, barely three months after succeeding Alhaji Adamu Attah of the defunct National Party of Nigeria (NPN).

The deceased left behind a country that is just trying to find its feet again under President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, his compatriot during the anti-military rule campaign. He bade farewell to a divided pan-Yoruba socio-political group, Afenifere, where a deputy leader pronounced himself as leader when the leader, Pa Rueben Fasoranti, is still alive. He left behind an oppressed and marginalised Kogi West Senatorial District, which, in the absence of zoning, can only aspire to produce the governor in vain.

Although he claimed non-membership of any political party, which many of his admirers doubted, he was a distinguished chieftain of Afenifere, which joined other forces to float the severely bastardised, abused, rattled, and weakened platform, the Alliance for Democracy (AD).

READ ALSO: The Tinubu administration and its malcontents (2)

One significant pain of the heart for Adebayo was his apt description as a Yoruba northerner. He was neither an ethnic chauvinist nor a religious bigot. But the eminent politician never forgave the colonial masters for the improper grouping of tribes into divergent provinces without considering historical and cultural factors. The consequence is the identity crisis, which the affected Igbomina, Ebolo, Kaba, and Ijumu and a section of Lokoja people are still battling to resolve in Kwara and Kogi states.

Unlike the Aro of Mopa, Chief Sunday Awoniyi, who adjusted to the geographical accident of diverse tribal lumping, C. O. Adebayo, like ‘Mallam’ Bello Ijumu and Chief Sunday Olawoyin of Offa, complained bitterly. Indeed, Olawoyin sustained the fight for the regrouping of the Yoruba in that axis with the Southwest. So far, it has been a lost battle.

At a lecture in Lagos, Adebayo lamented the consequences. When the Southwest was growing and the Yoruba were savouring free education and other people-friendly policies and programmes of the then Premier Obafemi Awolowo, the opportunity eluded his people. But Awo managed to give some scholarships later to Yagba and Kabba youths later. Adebayo also lamented the disparity in the development pace and the obvious marginalisation of his kith and kin who found themselves in the northern region.

But he won other personal and political battles.

Adebayo became a commissioner by merit under the military rule. Since he had built a reputation as a university teacher, the military governor had a reservoir of respect for him. In the two ministries of Information and Economic Development, and Education, he added value to the administration.

He was part of the Ibadan/Ife group of intellectuals who were influenced by the Awoist credo. Other members were Bola Ige, Wumi Akingbonmire, Itsey Sagay, Samuel Aluko, David Oke, Banji Akintoye, Akin Omoboriowo, and Bode Olowoporoku. Some of them who later took active part in the Second Republic politics became members of the Committee of Friends, which metamorphosed into the UPN, led by Awolowo.

Adebayo’s election into the Senate underscored his popularity among his people. In the Senate, he was not a bench warmer. But the UPN Caucus, led by Senator Jonathan Odebiyi, could only bark from the opposition; it did not have the fangs to bite hard. The quality of legislative opposition was superb. But Nigeria would have benefited immensely if Awolowo were president. He was the best President the country never had.

However, the UPN itself came under stress as from 1982 when some chapters were torn apart by nomination politics. Deputy Governor Sunday Afolabi, Michael Omisade and Busari Adelakun challenged Governor Ige to a duel in Oyo State. In Bendel, Demas Akpore never saw eye to eye with Governor Ambrose Ali. In Ogun, Soji Odunjo started fighting Bisi Onabanjo. In Ondo, Akin Omoboriowo pulled out his supporters to fire salvos at Adekunle Ajasin. The party was in turmoil.

In Kwara, Adebayo challenged Olawoyin, and the party, right from the Ikenne home of Awolowo, was polarised. Understandably, the party leader threw his weight behind his old ally who suffered a lot of bruises for the Action Group (AG) in the repressive hands of the Northern Peoples Congress (NPC). Governor Lateef Jakande of Lagos, whose grandfather hailed from Omu-Aran, and Onabanjo backed Olawoyin for governor.

However, Ige, who had been involved in a similar battle with Archdeacon Emmanuel Alayande in 1979, donated his experience to Adebayo.

Twice were the shadow polls conducted by Adebodun Adewumi, a lawyer, and twice did Adebayo floor the old Action Grouper. At the third exercise, Awolowo painfully upheld the results, with a passionate appeal to Olawoyin to see it as democracy in action.

A post-primary crisis was unleashed on the Kwara chapter. Reconciliation became an uphill task. All the party elders supported Olawoyin. The delegates, and majority of them were the youth who were not fascinated by stories about Olawoyin’s heroic past – tilted the pendulum of victory for Adebayo. The matriarch, Mrs. Hannah Awolowo, and her friend, Alhaja Abibatu Mogaji, had to travel to Ilorin to pacify the supporters of Olawoyin.

When the UPN campaign train rolled into Kwara, Olawoyin’s supporters protested. Later, they deferred to Awo’s moral authority.

Adebayo knew the coast was clear for him to win. Already, there was also a storm gathering in Kwara NPN, the structure of the highly influential Senate Leader Olusola Saraki, who had sworn to abort the second term bid of the Ebira prince, Adamu Attah. The Wazirin Ilorin sealed a deal with Adebayo. NPN’s top-notchers, including the minister, Akanbi Oniyangi, warned that should NPN lose Kwara, Saraki would lose his honour. The kingpin ignored them and rallied his supporters to deliver Adebayo.

But three months later, the curtains were drawn on the young administration. UPN and NPN were ideologically different. Nobody could actually predict how Governor Adebayo would have successfully managed his benefactor in four years. In fact, he was denied the opportunity to prove his mettle as governor by the military. After the December 1983 coup, soldiers started harassing the political class in a bid to cow them into submission. The majority of them were banned from politics to give the new breed a wider space.

But Adebayo resurfaced on the scene in the botched Third Republic, particularly during the June 12 crisis. Having been a victim of military high-handedness before, he joined forces with pro-democracy agitators to demand the de-annulment of the historic poll won by Moshood Abiola of the banned Social Democratic Party (SDP).

It was his undoing. He was targeted for liquidation by General Sani Abacha’s men. He had to hurriedly leave Nigeria to evade arrest and possible assassination. His next point of call, unlike other compatriots who had extensive foreign contacts, was Ivory Coast, where he suffered until a visa was secured for him to travel to Canada. Adebayo never wavered in spirit as a NADECO chieftain.

But it was a lost battle. The annulment was not reversed. The symbol, Abiola, died mysteriously in detention. In 1999 when civil rule was restored, the majority of those who supported the annulment and the interim contraption headed by Ernest Shonekan found themselves in power.

Adebayo enlisted in the post-1999 battle for true federalism. When Afenifere was engulfed in a protracted crisis, he stood on the side of reconciliation and peace. He never wanted to act as a divisive and destabilising factor. In fact, Adebayo was being projected for future leadership within the ethnic mouthpiece. Up to now, Afenifere remains divided.

Due to his composure and peaceful disposition, no Afenifere member raised an eyebrow when he joined the Obasanjo government as Minister of Communications. He had insisted that he was not an AD chieftain. It contrasted sharply with the reaction of the group when Ige was made the Attorney-General and Minister of Justice. At the ministry, he presided over the privatisation of NITEL. Although the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC) invited Adebayo for questioning on the Siemens bribe scandal, there was no subsequent report indicating that he was incriminated.

As Adebayo, the gentleman politician, goes home, his memories as a progressive will linger for a long time, especially among those of his generation and those who came after them.